What I Did This Summer (and so far this fall)

Hello from downtown Mancos, Colorado, where a large crow (or maybe it’s a raven, I can’t tell the difference at a glance) is cawing from atop the baseball backstop at the park, the wind is scattering cottonwood leaves, and the windows of the pizza parlor are decorated with large images of anthropomorphized candy corns.

It’s a perfect time to talk about summer.

From late May through mid-August I was in Maryland, and a lot of the time, I was focused on this:

… which was bunion surgery on my left foot. I’d had surgery on my right foot in 2017, which was a bunionectomy plus two osteotomies (cutting bones and putting them back together) plus a plantar plate repair (cutting ligaments and sewing them back together) plus removal of a big Morton’s neuroma (a non-cancerous growth on the nerve).

Fortunately, my left foot pre-surgery wasn’t nearly as bad as my right, so a lot less needed to be done to it. But it was also crazy how less painful and debilitating of an experience it was. I had surgery in mid-July, and 37 days later, I was back in the van and on my way to Maine, where I was able to walk a mile or two on trails and gravelly sandbars. I’m pretty sure that 37 days after my 2017 surgery, I was still limping around in a protective boot, unable to go anywhere except my desk job and physical therapy.

The thing was that this year’s surgery was not only to correct a less severe issue, but it was a whole different type of surgery, involving three tiny incisions rather than one big one. In a bunionectomy, the bone is cut apart and then screwed back together in a better position. Even though the screws in my left foot are actually much bigger than the ones in my right (think deck screws vs. laptop screws), the pain in my left foot was only a fraction of the pain in my right… like 1/10th.

This time I also took advantage of my one-week post-surgery hydrocodone prescription to quit all caffeine (I’d been drinking a LOT of tea) and start a new diet — and I think that quitting caffeine may have been a more painful experience than the foot surgery, overall.

Coco, my parents’ cat, was very helpful in the recovery process. She came to my parents last winter but had spent most of her life in a barn, where she’d somehow managed to survive despite being totally deaf and having bad eyesight. She was an older cat, though no one knows how old. This summer she started weakening quickly, and she died in September. She is missed, but she seemed to enjoy the ten or so months at the end of her life that she got to spend in a safe, comfortable place with lots of affection.

I stayed in my parents’ guest room until mid-August because a) I had some surgery follow-ups and physical therapy, so I needed to stay in the area and b) it was absolutely disgusting outside and way too hot for me in the van, even at night.

Then in mid-August, it was time to head north.

This doesn’t look like much, but it’s actually the NYC skyline just before sunrise.

On this northern trip, I was accompanying my friends Melissa and Dave and their two kids. When the kids were young, Melissa and Dave decided to visit all the country’s national parks, and they’ve made impressive headway, including some more remote spots like the Dry Tortugas and less impressive-sounding ones like Cuyahoga Falls. Just recently, they got their own campervan. (I am thrilled about this, and also please note and consider that I want all my friends and people I like to get livable vehicles so we can hang out in the woods/mountains/desert/park/wherever.)

I stopped to do some work in a small city in the Hudson Valley (which was really appealing and which I’ll have to check out later), then drove up to our rendezvous point in southern Vermont.

First time I’ve ever seen a porcupine in the wild — it was actually in an old graveyard inside the national forest!

Once Melissa and Dave and their family made it up north, we explored two sets of mountains: Vermont’s Green and New Hampshire’s White. The Green are softer, with denser woods; the White are more rocky and rugged, with some more dramatic dimensions and geology. I’d love to go back to the White Mountains just for hiking at some point.

But one of my biggest motives for writing this blog post is: I need you to know that off Route 11 in rural southern Vermont, there is a hair salon. The name of the hair salon is I’ll Cut You.

That is all.

We drove to Acadia National Park in Maine. Because I’m a lucky asshole, I’d been there twice before. Melissa and Dave had been there once before, but it was the first time for the kids.

There was a snail race.

And we did Maine Things, like eat seafood at a restaurant on a pier.

Sometimes people are surprised when I tell them I don’t go to national parks very often. They’re amazing places, but they’re generally not super livable for nomadic folks. Cell phone/data coverage for work can be nonexistent or spotty. The campgrounds are often full, they can feel quite busy compared to a middle-of-nowhere dispersed spot in a national forest, and they require reservations and advance planning. Plus, they’re expensive by my standards ($30+ per night), and then there’s a park entrance fee on top of that. (This year, since I knew I was going to several national parks, I got the annual pass to cover entrance fees, which at $80 is a pretty good deal — and the same price, I think, as when I took my first cross-country road trip in 2002!)

So when I do go to a national park, it definitely feels like I’m on vacation. And I really liked the campground at Acadia, which felt a little more spacious and relaxed despite being absolutely huge with hundreds of spots. But probably the best thing about staying inside the national park is that it gives you night access. Melissa came up with a brilliant idea for seeing Thunder Hole, a narrow crevice in the rocks where the waves go BOOM about an hour before high tide if the wind and waves are intense enough. Thunder Hole is wonderful but it’s one of the most heavily visited spots in the park, with crowds of people jostling around so you can barely see the Thunder Hole itself. Often, during the time/tide window when the Thunder Hole might be thundering, the parking lot is full.

So we just went at night! For something like Thunder Hole, where so much of the experience is sensory but not necessarily visual, this was awesome. We turned our headlamps off to stand there with the waves and the dark for a minute, then turned them on to spotlight Thunder Hole as the water sucked back and crashed over the rocks. And there was absolutely no one else there — no pressure to move over, move on.

It does sadden me to report that one of my favorite ever road signs, the one that said “THUNDER HOLE RESTROOMS,” has been removed. It has been replaced with a sign that simply has the restroom graphic and is thus much less satisfying to make stupid jokes about. R.I.P., Thunder Hole Restrooms sign.

Normally, on a trip like this, I would’ve wanted to do a Big Hike, but since my foot still wasn’t ready for that, we went sea kayaking instead. This was wonderful. We didn’t go super far, only a few miles, but I really loved being out there on a beautiful day, especially when we got into the channel between the islands, where there were some gentle but large swells. I’ve paddled in Chesapeake Bay rivers when they were kind of choppy, but never in any actual waves, and I liked the feeling of it.

On our last morning in the park, we drove up Cadillac Mountain to watch the sun rise. Melissa and Dave had to go back to Maryland so the kids could start school the following week, but I was able to stay in Maine for a couple more days. So I drove up the coast to Machias. This was the farthest north I’ve ever been in Maine, and I really liked the area. It’s less trafficky, less busy, but the coast is still absolutely beautiful. Plus the town of Machias itself seems pretty nomad-friendly, with two town-owned parking lots that are set next to a lovely river and where overnight parking is explicitly allowed. I’d taken time off of work for the Acadia trip, so in Machias I did just work a lot, but I’d love to revisit this area and stay longer.

This is Jasper Beach. It’s known for its pebbles that make a wonderful sizzling noise as the waves roll in and recede. These pebbles are not actually jasper, but rhyolite.

Rock lobster!

On my last morning in Machias I went to this coastal preserve on the beach to do some work. When I got there, it was low tide, and folks were digging for clams on the exposed muddy flats, hundreds of feet below the high tide line. After a couple hours, it was time for me to go. I’d driven onto the beach, just below the highest high-tide line, on what looked like a strip of well-used, hard-packed sand and gravel. I’d had no problems getting onto the beach, but instead of putting the van in reverse for a hundred or so feet, I went to turn around — and backed off the hard-packed strip and into sandy gravel that was much softer than it looked.

Yes, I got my dumb ass stuck. Very stuck.

This was quite stressful since by this time the tide was coming in. Of course it was a Sunday and all the towing places were closed. My insurance’s roadside assistance was sending someone, but they were about an hour and a half away, maybe two.

There were two lines of seaweed on the shore, and I was in between them. A couple passing locals told me that the highest line represented a storm tide, and I would probably be out of the reach of the normal high tide, but this still did not feel reassuring. I tried to dig myself out, and I used the traction strips that I’d ordered for just this situation… but each time I tried to get out, the van just went in deeper. I couldn’t quite see what was going underneath, but I suspected the rear differential and/or the spare tire were actually resting on the ground, which would be… very not good.

Despite Machias’s frequent appearances in Stephen King novels, where the scariest thing is not actually the monster but the people, my experience with the people of Machias was bizarrely positive. Everyone who passed by seemed to offer help of some kind — they’d call their husband, who was probably out in the garden right now, but if he did answer the phone, might know someone who could help. Or they could call their friend not too far away who had a farm tractor, and maybe the tractor could lift the van out of its hole. With the tide rising quickly and the tow company still hours away, I did take someone up on their offer — a young couple who’d come to the beach to walk their dogs. The guy’s father lived a few minutes up the road and had a big truck.

Even with the big truck, it took a while (and a couple of calls to the guy’s high school buddy’s dad Timmy, who owned a towing company) to figure out how to get me out. There actually aren’t any good points on the front end of my van to attach a tow hook (which seems like a big oversight), and I was worried that if they tried to pull me out backwards, it would just pull the rear axle/spare tire/exhaust system/bumper into the gravel. Plus if that towing attempt failed, it would put me much closer to the incoming water.

Finally I got desperate enough to say OK to being pulled out backwards. And… it worked. There were a couple of scuff marks on the rear differential and a bunch on the spare tire, but the van seemed undamaged. There were high fives all around, and even though I will never willingly repeat this experience, I’ve gotta say that the adrenaline rush of having your home threatened by an inexorably incoming tide, and then getting away from it, is really something else.

Once I was safely above the highest high tide line, my rescuers and I (native Mainers whose names are Riley and Joelle; Riley is an actual lobster fisherman) stood around and chatted for a while. Then I filled in the big holes I’d made in the beach and was on my way. I plan never to drive onto a beach again.

This pic was taken from about the same spot as the earlier photo on the beach; note how much closer the water is!

I had a doctor’s appointment in Maryland and a bunch of work to do, so I made my way south over two days: the first evening I stopped at my friend Sarah’s in the Finger Lakes region of New York, and the next at my friend Sasha’s in South Jersey. I wish I could’ve stayed longer in both cases, but it was great to be able to catch up a little bit.

I spent another week in Maryland, full of logistics, medical appointments, and way too much dental work. (One of my old root canals failed, which cost over $2300 to fix and my dental insurance covered none of it. The fact that dental work is so expensive and that teeth are considered luxury bones that are not covered by insurance in any meaningful way is very upsetting to me, and I think that the next time I need a root canal or re-root canal or new crown or anything like that, I’ll just have the tooth pulled and then go to Mexico and get it replaced with an implant.)

It was a stressful week, but I did get to do some Maryland Things: make air fryer crab cakes, hang out in my friend Meg’s hot tub/on her porch, and go paddling with my mom on the bay.

In early September, I got on the road again, this time headed south. I met up with my friend Ron in South Carolina and we visited Mepkin Abbey, a Trappist monastery.

Ron stayed at the abbey for the full residential retreat experience, while I camped nearby with his dog Puck and just came to the monastery in the daytime.

The live oaks at this monastery are some of the most incredible trees I have ever seen.

After Mepkin, Ron headed back south to Florida and I turned west, where I got to spend a couple nights with my brother and his family at Lake Oconee in north Georgia and at their home in Atlanta.

Then, I headed west…

And now I’m in the San Juans, in southwestern Colorado. I missed being out here this summer, and it’s been a busy October so far, with tons of work — but I’m glad I’ve gotten to spend at least a couple weeks out here before it gets too cold. Already I’ve had one below-freezing night, up at about 9,200 feet in the West Dolores River valley.

But it was absolutely worth getting up in the cold to be able to go out hiking and watch the sun hit the peaks.

And the trees… I just can’t even deal with it.

How is this real???

1917, 1947, or 1941?

And yes, my phone is about 90% photos of trees and mountains.

I need to head back into the woods now, but sometime soon I hope to post about staying warm when living in a van — a topic that I’ll need to give more thought to in just the next couple of weeks!

The Island

In the river by my parents’ house in Maryland there is an island. It’s not big, only about fifteen hundred feet long and a couple hundred feet wide at its widest point. But it’s dramatic: on its south side, sandy cliffs rise out of the water. It’s topped with tall, twisted loblolly pines and tangles of climbing vegetation. On the north side, there’s a long, sandy beach where the water deepens gradually, a perfect swimming spot.

Growing up, I knew this island as a wild place. My parents would take me and my brothers there and beach the boat, and when each of us got old enough, we were allowed to wander around the island on our own. There was only one way up off the beach to the island’s raised interior: a scramble up a steep, sandy, eroding hill. Once I was up there, I felt as if I’d left the world I knew behind and stepped into a much more expansive one. This could be what it looked like just after the dinosaurs went extinct: golden light slanting through pines, cicadas buzzing in the jungly vines, and ospreys calling — which basically sound like longing made audible. I spent hours up there, standing just far enough back from/close enough to the cliff that I felt the exact right amount of danger, or following the trail (there was only one trail, really, on such a narrow island) until I lost it in the vines.

And then a group of other people in bathing suits and flip-flops would tromp past, the adults talking loud and the kids sticky-mouthed, and for a minute it would break my illusion of being the only person for a hundred miles.

Despite feeling so primeval while I was up there, this island, Dobbins Island, was and is totally enmeshed in our human times. It’s been a party spot for well over a century, since the time when the sandbar was still close enough to the river’s surface to drive a horse-drawn carriage from the mainland to the island at low tide. At one point, someone had built a stone house on the island, which lasted for a while and then crumbled away. (One summer, in the most viney part of the island, a friend and I found a round stone cistern set into the ground, with some scummy green water at the bottom, and part of what could be a foundation. We could never find it again.) Just a little before my childhood, the island was apparently an exchange point for cocaine smugglers: the cargo was landed in float planes and transferred to waiting boats. And since my childhood, summer weekends mean that the island’s shallow anchorage is full of boats. People everywhere, with pool floats and super-soakers and coolers full of soda and beer. Sandwiches, boomboxes, cigarettes, sunscreen.

When I was growing up, I understood that the island was owned by a family who had held it for a few generations. There was some kind of complicated legal structure involved, and family members who did not get along. They could, if they wanted to, put up “No Trespassing” signs, or a fence, or houses, at any moment. The only reason I was able to enjoy this place was because the owners lacked the motivation or unity of will to kick people, the public, off of it. By the time I was in middle school, I was aware that the island as I knew it might not last forever.

It lasted through my high school years, and my brothers’. But in the early 2000s it was sold, and soon after, the new owner put up the “No Trespassing” signs. It was rumored that he wanted to build a house.

Each step of the process was marked by some kind of controversy or resistance: people called for the county/the state/a local conservation group to buy it and make it into a park, or better yet, just keep it as it was. At one point, a fence went up to keep boaters off; there was a legal dispute, and the fence was removed.

In most states, including Maryland, the rule is that the public has a right to be on any beach or shoreline as long as they stay below the mean high tide line. Below that line, landowners have no legal right to bar people from beaching a boat, building a sandcastle, or sitting in a chair with their feet in the water. Even if there just so happen to be a few dozen people, or a few dozen boats full of people, or, as reported in 2011, over 800 boats full of people at the annual “bumper bash” party.

About a decade ago, the island’s new owners finally built the house and a long pier. Fortunately and unlike what happened in the case of a smaller island nearby, the owners at least obeyed zoning and environmental restrictions, so from the water, aside from the pier, the island hasn’t changed too much. In the summer, the trees mostly screen the house from view.

I paddled around the island a few weeks ago in a friend’s kayak. Four or five ospreys circled or roosted in the trees, and kingfishers — a beautiful bird I never saw on the river growing up — have dug holes in the cliff to nest in. It’s still beautiful, and there’s still a sense of wildness about it, and also a sense of accessibility — at least below the mean high tide line. It could still be a magical place for a kid, or an adult.

But of course I felt a sense of loss. Without access to the island’s interior — the scramble up the steep hill that marked one’s palms with clay, the breeze coming up from the river — I can’t get inside that wildness, either, not as fully as I once could.

And the time I’ve spent in the west recently heightens that contrast. This spring, I spent a little time in Utah and more time in Colorado, with a trip to Death Valley and Canyonlands national parks in there as well, and these are all places where the dynamics of wild places and public land are very different. There’s public land in the county where I grew up, and some of it is still just trees with crisscrossing trails, but they’re smallish pockets of land, relatively, and the gates close at dark. There’s noplace within a two-hour drive where you could walk for a day without coming to the end of the trail, and of course there’s no public land where I can park my van and stay for free.

I was recently talking to a friend about the difference between wilderness and wildness. Wilderness is pristine, preserved; wildness just hasn’t been touched for a while. It could be an old clear-cut where the trees are growing back — not the irreplaceable old growth, but whatever species are up for the task — or an island with vines growing over the foundations of an old house. Maybe wildness could even be a very overgrown backyard, or any other space where human attention is mostly turned the other way and natural forces are dominant.

Wilderness — like Colorado’s 44 designated wilderness areas that I’m trying to hike — is something I only encountered as an adult. And I love it, obviously. But wildness is what I grew up with. Like the island, or like the woods next to my parents’ house. (This woods, too, is now fenced off and built up with boring and oversized houses, but before that, it was glorious.) These kinds of wild places — the marsh by the road,the yard where saplings grow around the wrecks of old boats and cars — feel charged with a unique kind of energy. They’re scrappy, the natural order fighting hard to stay or to make a comeback. As long as those places last, it feels like they’re getting away with something.

Another thing about wildness: it can be anywhere. Vacant lots, slips of suburbia too boggy or difficult to build on, or next to Cherry Creek in Denver where herons pluck fish out of the water in the shade of an overpass. When I took a train through Eastern Europe in 2006 I saw people picnicking on the slope above the train tracks, and I bet they were there for the wildness.

Right now I’m in Maryland, and to be honest, I’d rather not be. But I need foot surgery — nothing as big as the one I had in 2017, which involved two incisions, four cuts through the bone, four titanium screws, and a bunch of toe ligaments cut and then sewn back together — but still significant enough that I’ll need to stay in a normal house, not a van, for a few weeks. (I was trying to make this surgery happen in Colorado: I talked to a couple of surgeons there, who gave me two different surgical plans and I felt uncomfortable with both. But the surgeon here in Maryland who did my other foot five years ago came up with a plan I feel pretty good about.)

I’m not excited about having foot surgery. I’m not excited about going for the whole summer without hiking or stand-up paddleboarding, and I’m not excited about being unable to do normal life things, like lugging a forty-pound jug of water from the spigot to the van or even taking a shower, without caution and deliberate thought. I’m not excited about all the rehab I’ll have to do on my foot, because that involves a lot of stretching and stretching is boring and I hate it. I’m not excited about being unable to exercise like I’m used to and losing whatever fitness I’ve gained in the last year. But all of this had to happen sometime, and now’s the time.

So I’m looking for the silver linings. For one, I’m grateful that I have option of being able to stay in my parents’ nice guest room while I recuperate, with my mom to make sure I take the appropriate dose of painkillers and bring me food and water. For another, I’ve been able to see some friends and family members in person for the first time since before the pandemic. And though this part of Maryland lacks mountains, it makes up for it with water, and I’ve been able to paddle and swim. I’ve spotted horseshoe crabs from my parents’ pier, a deer eating the old lettuce my mom threw out, a bluebird feeding its baby with a seed from the bird feeder. So right now I miss being in the wilderness — but I have wildness.

44 Wildernesses

I’m a sucker for maps.

Maps are mystery. Maps are potential.

Looking at a map, planning where I might go, what areas I think might be beautiful or interesting or might simply fill in the blank spots in my own mental map, is weirdly satisfying to me. I find looking at maps of places I might go hiking almost as good as actually being out there — or even better than being out there, if it’s chilly outside and I’m wrapped in blankets, daydreaming.

So check out this one.

This is a map of all the wilderness areas in Colorado, shown in darkest green.

There are a lot of them. Forty-four, to be exact. And last summer, when I was making loops all over the state, hyped up on the novelty of being able to go wherever I wanted, I decided: I’m going to hike in all of them.

It doesn’t have to be anything crazy, like an overnight backpacking trip or even an all-day thing. Just a mile or so past the wilderness boundary, enough to give me a taste of the place, will do.

Not only would this be fun, I figured, but it could be a helpful organizing principle. Sometimes having an enormous amount of options makes it paradoxically harder to make decisions. And trying to set foot in each of the wildernesses could get me thinking outside the scope of what I already know. So I figure that if I ever want to go someplace in Colorado that’s new to me but am not quite sure how to narrow it down, I can take a look at the list of wildernesses and go where I haven’t been yet.

So, you may wonder, since I spent like five whole months in Colorado last summer, and there are 44 wildernesses, and I just wrote in my last blog post about how I’ve been doing too much driving, I must have been to what, half of them by now? A third?

Nope! I’ve been to seven. (So that’s a tiny 6.29%!)

I’m not in a big hurry on this. I want to try to avoid the urge to rush from one place to another, and I want to drive less, like I mentioned. Also, I want to make sure that I don’t, just to give a totally hypothetical example that absolutely isn’t taken from my actual life at all, nope no sir not me, procrastinate from difficult good things like writing fiction by focusing on easier good things like hiking.

So here’s my list as it stands:

WILDERNESSES HIKED IN

Sangre de Cristo

- Venable Trail

Lizard Head

- Navajo Lake

- probably Lizard Head Trail crossed wilderness boundary

Holy Cross

- Timberline Lake

- St. Kevin Lake

Mt. Massive

- Windsor Lake

Flat Tops

- Chinese Wall

- Devils Causeway

Raggeds

- Raspberry Creek

Hermosa Creek

- Ryman Trail to Highline/CO Trail

Let me tell you about the one I added to my list yesterday, Hermosa Creek.

This wilderness is in one of my favorite areas of the state: the San Juan range in southwestern Colorado. I’ve written before, I think, about the San Juans. They get a bit more summer moisture than some other ranges, so by Colorado standards, they’re very green, and the rocks and soil can be very red. They used to be volcanoes, and there’s something about the mud that is extra silty and sticky, so each of your boots end up weighing like five pounds. The western region of the San Juans, which is where I’ve spent the most time, also has some really sudden transitions from farmland to mountains or mountains to desert, and I am all about that drama.

I spent the first couple weeks of May in the national forest north of Mancos, so I wasn’t too far from the Hermosa Creek Wilderness, which is one I was very curious about. But it’s not easy to access. There are no roads close by on the east or north, and while there’s a road going towards it from the south, I went a little bit up that road last fall, and I suspect that the last few miles of it wouldn’t be navigable with my van. So I’d be walking a few miles along a 4wd road, possibly eating the dust of passing ATVs, which does not seem fun.

I opted instead to hike into the wilderness from Route 145 just south of Rico, one of my favorite mountain towns. (And where I’m parked now as I’m writing this blog.)

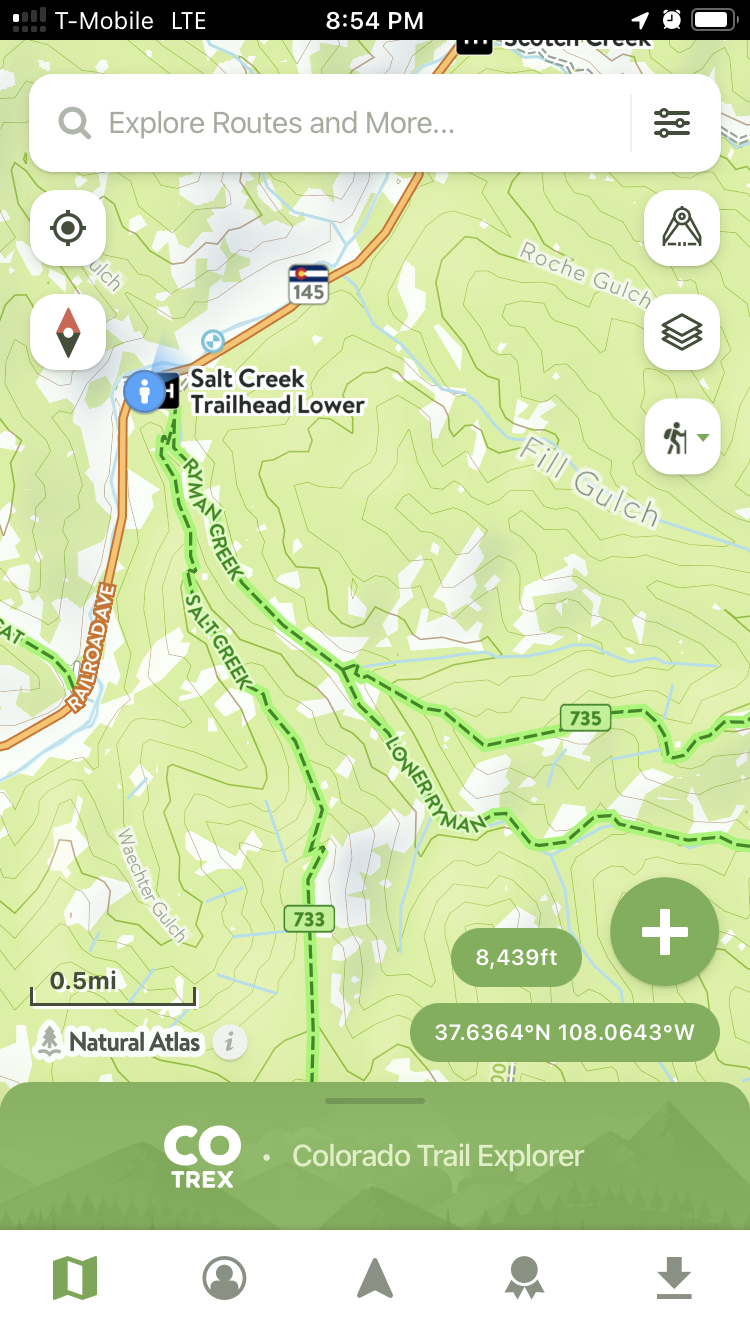

I’d take the Ryman Creek trail. As I headed east, I’d stay left at the fork to go on Upper Ryman, then turn right/south for just a teeny tiny bit until I got to the wilderness boundary. (Which is the line made up of a bunch of green dots in the lower-right corner of the second photo.)

This plan was a little tentative. There’s still some snow in patches high up, and I’d tried hiking Lower Ryman last fall and it was pretty overgrown. Also, a couple people on the Alltrails app mentioned that Upper Ryman was “steep” (which really could mean anything, from “a sphere placed on this surface would roll downhill” to “you will need to use your hands to climb up it”). I figured that if things got too tricky before I got to the wilderness boundary, I’d just turn around and at least I’d have a nice hike anyway.

I started out at the ass-crack of dawn, around 6 a.m., because even though I’m a natural sunrise-waker-upper and it takes some effort for me to get up before sunrise, once I’m out there and it’s still so early that the light is gray, I adore it. About a mile or so up, I came to my first obstacle.

Uh oh! It’s a spiky log!

The water in the creek was pretty high due to the snowmelt higher up. Last fall, I think I just stepped across the creek where it went between the two evergreens (upper left of photo) on some raised logs or sticks or hummocks of grass. But this time, it was either spiky log or get my feet wet. I opted for spiky log, and I did it!

Soon afterwards, I passed this sign.

I never did see any trail construction, but I did periodically wonder what the sign meant by “and even worse.” Did they mean that those who failed to obey the sign would be punished by a fate worse than death? Or just that a person could cause a rockslide and kill someone else, which might be worse for the rockslide-causer than if they themselves died? Or did whoever wrote this sign just want to keep us on our toes?

Then the steep part started. And it was steep. I didn’t have to use my hands, but I was hauling myself up using my hiking poles. And I did think, “this particular angle is the limit at which a human foot can maintain traction on this particular surface.” The trail surface was just dirt, which was sometimes loose and slidey. I would’ve had a much better grip if it was solid rock, or it would’ve been an easier climb if there were rock steps or switchbacks. But the trail went up a relatively narrow ridge, so in many spots there wasn’t even room for switchbacks. So the trail just went straight up the spine.

I didn’t take many photos because I was busy cursing and being out of breath and trying not to slip. It was really beautiful, though.

Once the steep section was done, I found myself in a magical aspen grove.

I took a break here to drink a bunch of tea and eat a snack. The birds had woken up in earnest when the sunlight hit the ridge, so I was using this new app that I am obsessed with that identifies birds by sound. There were some sweet little warblers, a northern flicker, and a flock of at least half a dozen violet-green swallows. These swallows were wonderful to watch, darting and banking and diving and soaring out over the creek valley. I don’t think they were catching bugs, not as early and chilly as it was. I’m sure that a bird behaviorist could explain why they were doing that and that it must have a survival function—reinforcing group roles and hierarchy, or competing for mates, something like that—but it looked like exuberance, like play.

Definitely not my photo, but just so you can see how gorgeous these birds are:

The top of the ridge was mostly aspen (with a few stands of evergreens) for miles. It was just beautiful up there, and I had some interesting wildlife moments. Tons more birds, for starters. Then I heard a snap or crash and in the distance between the trees saw something large and brown running down the hill. It was either a deer, elk, or bear—all of which had left tracks on the trail at some point—but it was clearly aware of me long before I was aware of it. Later on, a hummingbird came out of nowhere and arrowed towards me. I thought it was going to pass over my head but it stopped, going sixty to zero, about two feet in front of my face, and stared at me, flaring its tail. Then it zipped away. For the Aztecs, hummingbirds and warriors were connected, and this makes total sense.

The aspen trees were heavily marked, and most of those markings were so old they were no longer legible. I get the sense that decades ago, this trail saw heavier use than it did today. I’m not keen on people carving their names into trees, but it is pretty impressive how old some of these trees are!

I kept going gradually up, passing the turnoff for the Lower Ryman trail, and then there was another, shorter section of steep climbing. More of the surrounding ridges and mountains came into view—off to the south, I could even see Dibe’Nitsaa (aka Mt. Hesperus), which is a few miles away from my last campsite north of Mancos.

Then I came to the next obstacle:

There was snow covering the trail. I thought, if it’s like this the whole way, I won’t be able to slog through it all. I might have to turn back. Fortunately, the snow was just a few patches, 10-20-30 feet long, and it was still frozen solid enough at that point that I mostly just walked over it.

Then it all happened very quickly: I got to the forest service road that led to the Highline Trail/Colorado Trail. Then I was at the Hermosa Creek Wilderness boundary!

I know I said that I liked to walk about a mile past the boundary. But the trail here never actually crosses it, and it was a fairly long hike to even reach the boundary. So in this case I was content with just walking around the sign.

But the big thing happening here was the views.

Enhance!

I mean, why? Why is it like this??

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

[inward shouting of incomprehension and delight]

But because language gives us a tool to make sense of things, I can say that part of what boggles me about a mountain range like this one is that there’s both incredible scope and incredible intricacy. Like nature should be exhausted after making *one* mountain that complex and that huge, but there’s another and another and another and…

And there’s also the time scale: the knowledge that in the deep past, if you could sit where I was sitting and watch that specific sector of the horizon for ten years, twenty, a whole lifetime, probably nothing visibly dramatic would happen. And yet, the drama! It looks like they just popped out of the ground last week, all crowding together in their eagerness to start being mountains and do an EMPHATICALLY good job of it.

And because one way we engage with mystery is to make maps, and measure things, and give the mountains names, even when there are so many and they are so big, I can tell you that the mountain range in the distance was about 20 miles from where I was sitting, that on the map it’s called the Needles range, and that these are some big honking mountains.

Even though I could’ve stayed there for hours, after about 45 minutes of sitting and looking and eating a couple of tortillas with peanut butter, I had to start back. I picked up a couple pieces of litter (yes, even all the way up there), tried talking to a raven, and it was literally all downhill from there.

Also literally, it was a very enjoyable walk downhill. I did encounter a few obstacles:

The snow had softened, so it didn’t hold my weight so well and I postholed through it thigh-deep a few times. Totally worth it.

I slipped crossing a tiny stream and landed on my ass in the San Juan mud. Also totally worth it.

Going down the steep sections of the trail was trickier and more dangerous than going up, and my feet went out from under me once or twice. Fortunately I didn’t hurt myself, and still totally worth it.

I’m a slow hiker, I stop often to stare at things, and I take long breaks, so about 12 hours after I left the van, I came back to it tired, hungry, muddy, exhilarated, and content.

So that’s how I hiked into my seventh Colorado wilderness. Here’s to 37 more.

By the Numbers: One-Year Retrospective

This past Sunday (May 8) was Mother’s Day this year, but it also happened to be my one year (v)anniversary of living full-time and continuously in van v2.0. Counting the time I lived in v1.0 (September–December 2020), it’s been 16 months. So it seems like a good time for a very math-y perspective on how it’s going so far.

I had to start by thinking about miles traveled. Since I bought the van with (I think) about 298,000 miles on the odometer, I’ve put about 31,000 miles on it, averaging 1,937.5 miles per month. Given that the average driver covers a little over 1,100 per month, that’s a lot.

It also means I’m generating about 2,700 lbs of CO2 emissions each month, which—well, I’d really rather not. (I’m paying a shockingly low amount ($23) per month to offset 5,000 lbs of CO2 through Terrapass, though I’m not sure how effective this carbon offset program or any other program is at compensating for the damage I’m doing.)

I tried to use Google Maps and then Mapquest to draw my approximate route since May 2021, but Google Maps wouldn’t let me add enough stops and Mapquest failed to compute the route past November 2021. So you’ll just have to imagine it:

I’ve been as far northwest as Seattle; as far southwest as Death Valley, CA; as far southeast as metro Tampa, FL; and as far northeast as South Jersey. Colorado would end up looking like a hub: and I’ve looped around the mountain ranges in the north and south of the state. I’ve also made sort of a Y-shape in New Mexico and visited Capitol Reef and Arches National Parks in Utah.

Am I Better Off?

When I decided to move into a van, I was hoping for a couple of things: a) that it would help me save money, or at least break even, and b) improve my quality of life.

So it’s time for some van-cost calculations that I’ve put off for a year, simply out of dread of what I’ll see when I look through my old credit card statements: the fast-food breakfasts; the four single-serve kombuchas in a two-week period when a large bottle would have been cheaper and buying none at all would have been more responsible; all the orders from mega-retailers that are destroying individual lives and the world in general and profiting space billionaires; and my general moral decline from my financially-disciplined, I-know-where-every-cent-is-going teens and twenties into my weak-willed, effete, flabby middle age.

But deep breath. Here goes.

Did I Save Money on Housing?

Base cost of van (purchase, registration, initial repairs): $2,801.17

Professional help with build (solar, removing rear AC/heat units): $1,898.72

Build supplies (including lumber, battery, fan, insulation, hardware, mattress, etc.): $6,764.54

Repairs, maintenance (not counting oil changes), upgrades (fancy tires): $3,685.39

TOTAL: $15,149.82

Honestly, despite my initial hope of keeping the whole van under $10k, $15k is about what I was suspecting. And I’m guessing it’s more than I’ve spent, total, on all the other cars I’ve ever owned in my life. (Which were all compact sedans or hatchbacks that I bought used and drove until the wheels fell off, metaphorically speaking.)

So to me, $15k sounds pretty cheap for a house… but a LOT for a car… but cheap for a house! I don’t know what to think!

But I still need to factor in travel costs. Some Googling and some very loose math tells me that the average cost of gas since September 2020 has been $3.50.

Doing another calculation I’ve been dreading, I find that the van gets an average of 13.24 miles per gallon, which is not as bad as I was afraid of, but not great.

31,000 miles @ 13.24 per gallon = 2,341 gallons x $3.50 = $8,193.50

So here’s the grand total cost of living in a van since September 2020:

Van total: $15,149.82

Driving all over the place: $8,193.50

Campgrounds (estimate): $520

—————————————————————

TOTAL: $23,863.32

Now let’s compare that to what it would’ve cost me if I stayed in my Denver condo. I’m assuming that I’m spending about the same on food, entertainment, healthcare, laundry, car insurance (the van is a little more than my old car, but not that much), etc.

Condo mortgage + HOA fees + average electric, September 2020-present: $715 x 16 = $11,440

OK, so that sucks. Living in a van has not saved me money on housing.

In fact, it’s cost me $12,423.32 more.

But the van had some big initial costs that I hopefully won’t encounter again, like the initial purchase price and all the stuff for the interior build. So is there ever a point where I’ll break even financially?

Yes, there is. But—assuming that I continue to drive an average of 1,937 miles/month, that the price of gas stays the same as it is right now ($4.10), and that my condo HOA fees would not have gone up—the break-even point won’t be until 2031.

:/

But what if I drove less? Say I could reduce driving by 1/3. That moves the break-even point to 2026. Which is better than 2031… but still not super.

Things become slightly better if I reduce driving by 1/2: I’d break even in early 2025. The same could happen if I reduce driving by 1/3 but gas goes down to $3.50/gallon.

So the news here is not great: If I ever want to break even, I need to start driving less.

Did My Quality of Life Improve?

So all my cost estimates assume that nothing major will go wrong with the van (knock on wood) and that nothing major would have gone wrong with my condo. It also assumes that if I’d stayed in the condo, I wouldn’t have traveled beyond some occasional day trips or camping trips into the Colorado mountains.

Which brings me to the next question: has living in a van been better, in other ways, than living in a condo?

I wish I could do math for this too. (And if you know of a more rigorous way to measure quality of life, message me!) But all I know to do is make an old-fashioned pros and cons list:

Living in Condo

Living in Van

It’s tough to make a meaningful comparison here without the ability to see into a parallel universe where I’d stayed in the condo. Maybe, in the last year-plus, I would’ve found some ways to alleviate the negatives of staying in the condo: maybe an amazing career opportunity would have opened up, quieter neighbors would have moved in, or something totally unexpected and great would happen.

Also, it wasn’t a binary choice between van and condo. I was considering some other options, like moving onto a boat in Baltimore or a small house somewhere in the desert or the rural midwest. Maybe those options would’ve been much better than the van… or much worse.

All I know is that even though I’m pretty disappointed that I’m not saving a ton of money over the condo, I feel like my quality of life is better than it would’ve been if I’d taken the other, obvious path of staying put. Even though the van has a ton of drawbacks, the positives have some heft to them. My stress level seems lower than it was when I lived in more “normal” places. I think I’ve gotten healthier and am in better shape. And I enjoy being “at home” more. (And if I decide that I need to make cutting costs more of a priority, I can quit at any time! Really! (Do I sound convincing? I’m not so sure that I do.))

I’ll end with a caveat, if anyone is reading this out of curiosity about what a nomadic life costs: this blog post uses a sample size of one to obtain its data. I imagine that some people spend much more every year; I know for a fact that many spend far less. The Homes on Wheels Alliance (HOWA) is a great resource for nomadic life on a budget. One of their videos features a guy whose total expenses (minus the initial cost of his RV) are under $4k/year, and other folks talk about how they live within their means on fixed incomes like social security. (The Glorious Life on Wheels channel also features folks on fixed incomes and talks about how that works.) So low-budget vanlife can be done… I’m just not doing it.