44 Wildernesses

I’m a sucker for maps.

Maps are mystery. Maps are potential.

Looking at a map, planning where I might go, what areas I think might be beautiful or interesting or might simply fill in the blank spots in my own mental map, is weirdly satisfying to me. I find looking at maps of places I might go hiking almost as good as actually being out there — or even better than being out there, if it’s chilly outside and I’m wrapped in blankets, daydreaming.

So check out this one.

This is a map of all the wilderness areas in Colorado, shown in darkest green.

There are a lot of them. Forty-four, to be exact. And last summer, when I was making loops all over the state, hyped up on the novelty of being able to go wherever I wanted, I decided: I’m going to hike in all of them.

It doesn’t have to be anything crazy, like an overnight backpacking trip or even an all-day thing. Just a mile or so past the wilderness boundary, enough to give me a taste of the place, will do.

Not only would this be fun, I figured, but it could be a helpful organizing principle. Sometimes having an enormous amount of options makes it paradoxically harder to make decisions. And trying to set foot in each of the wildernesses could get me thinking outside the scope of what I already know. So I figure that if I ever want to go someplace in Colorado that’s new to me but am not quite sure how to narrow it down, I can take a look at the list of wildernesses and go where I haven’t been yet.

So, you may wonder, since I spent like five whole months in Colorado last summer, and there are 44 wildernesses, and I just wrote in my last blog post about how I’ve been doing too much driving, I must have been to what, half of them by now? A third?

Nope! I’ve been to seven. (So that’s a tiny 6.29%!)

I’m not in a big hurry on this. I want to try to avoid the urge to rush from one place to another, and I want to drive less, like I mentioned. Also, I want to make sure that I don’t, just to give a totally hypothetical example that absolutely isn’t taken from my actual life at all, nope no sir not me, procrastinate from difficult good things like writing fiction by focusing on easier good things like hiking.

So here’s my list as it stands:

WILDERNESSES HIKED IN

Sangre de Cristo

- Venable Trail

Lizard Head

- Navajo Lake

- probably Lizard Head Trail crossed wilderness boundary

Holy Cross

- Timberline Lake

- St. Kevin Lake

Mt. Massive

- Windsor Lake

Flat Tops

- Chinese Wall

- Devils Causeway

Raggeds

- Raspberry Creek

Hermosa Creek

- Ryman Trail to Highline/CO Trail

Let me tell you about the one I added to my list yesterday, Hermosa Creek.

This wilderness is in one of my favorite areas of the state: the San Juan range in southwestern Colorado. I’ve written before, I think, about the San Juans. They get a bit more summer moisture than some other ranges, so by Colorado standards, they’re very green, and the rocks and soil can be very red. They used to be volcanoes, and there’s something about the mud that is extra silty and sticky, so each of your boots end up weighing like five pounds. The western region of the San Juans, which is where I’ve spent the most time, also has some really sudden transitions from farmland to mountains or mountains to desert, and I am all about that drama.

I spent the first couple weeks of May in the national forest north of Mancos, so I wasn’t too far from the Hermosa Creek Wilderness, which is one I was very curious about. But it’s not easy to access. There are no roads close by on the east or north, and while there’s a road going towards it from the south, I went a little bit up that road last fall, and I suspect that the last few miles of it wouldn’t be navigable with my van. So I’d be walking a few miles along a 4wd road, possibly eating the dust of passing ATVs, which does not seem fun.

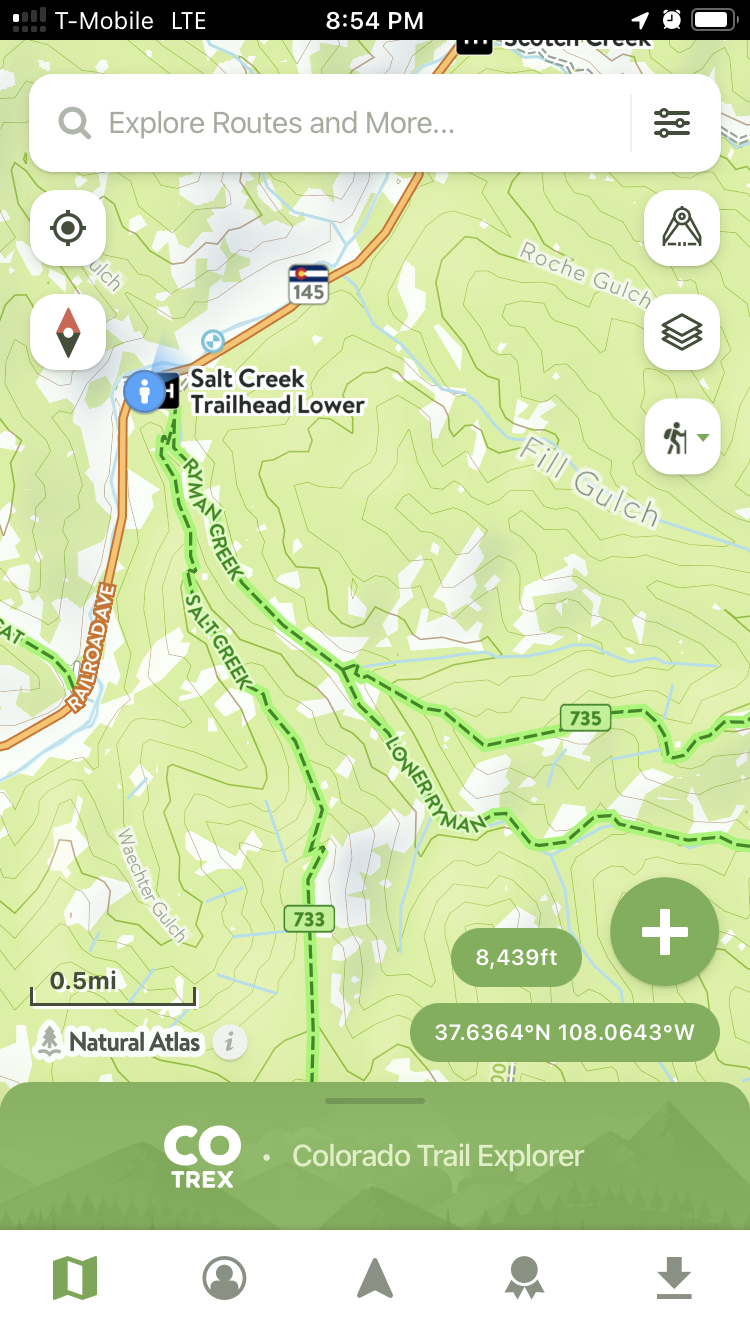

I opted instead to hike into the wilderness from Route 145 just south of Rico, one of my favorite mountain towns. (And where I’m parked now as I’m writing this blog.)

I’d take the Ryman Creek trail. As I headed east, I’d stay left at the fork to go on Upper Ryman, then turn right/south for just a teeny tiny bit until I got to the wilderness boundary. (Which is the line made up of a bunch of green dots in the lower-right corner of the second photo.)

This plan was a little tentative. There’s still some snow in patches high up, and I’d tried hiking Lower Ryman last fall and it was pretty overgrown. Also, a couple people on the Alltrails app mentioned that Upper Ryman was “steep” (which really could mean anything, from “a sphere placed on this surface would roll downhill” to “you will need to use your hands to climb up it”). I figured that if things got too tricky before I got to the wilderness boundary, I’d just turn around and at least I’d have a nice hike anyway.

I started out at the ass-crack of dawn, around 6 a.m., because even though I’m a natural sunrise-waker-upper and it takes some effort for me to get up before sunrise, once I’m out there and it’s still so early that the light is gray, I adore it. About a mile or so up, I came to my first obstacle.

Uh oh! It’s a spiky log!

The water in the creek was pretty high due to the snowmelt higher up. Last fall, I think I just stepped across the creek where it went between the two evergreens (upper left of photo) on some raised logs or sticks or hummocks of grass. But this time, it was either spiky log or get my feet wet. I opted for spiky log, and I did it!

Soon afterwards, I passed this sign.

I never did see any trail construction, but I did periodically wonder what the sign meant by “and even worse.” Did they mean that those who failed to obey the sign would be punished by a fate worse than death? Or just that a person could cause a rockslide and kill someone else, which might be worse for the rockslide-causer than if they themselves died? Or did whoever wrote this sign just want to keep us on our toes?

Then the steep part started. And it was steep. I didn’t have to use my hands, but I was hauling myself up using my hiking poles. And I did think, “this particular angle is the limit at which a human foot can maintain traction on this particular surface.” The trail surface was just dirt, which was sometimes loose and slidey. I would’ve had a much better grip if it was solid rock, or it would’ve been an easier climb if there were rock steps or switchbacks. But the trail went up a relatively narrow ridge, so in many spots there wasn’t even room for switchbacks. So the trail just went straight up the spine.

I didn’t take many photos because I was busy cursing and being out of breath and trying not to slip. It was really beautiful, though.

Once the steep section was done, I found myself in a magical aspen grove.

I took a break here to drink a bunch of tea and eat a snack. The birds had woken up in earnest when the sunlight hit the ridge, so I was using this new app that I am obsessed with that identifies birds by sound. There were some sweet little warblers, a northern flicker, and a flock of at least half a dozen violet-green swallows. These swallows were wonderful to watch, darting and banking and diving and soaring out over the creek valley. I don’t think they were catching bugs, not as early and chilly as it was. I’m sure that a bird behaviorist could explain why they were doing that and that it must have a survival function—reinforcing group roles and hierarchy, or competing for mates, something like that—but it looked like exuberance, like play.

Definitely not my photo, but just so you can see how gorgeous these birds are:

The top of the ridge was mostly aspen (with a few stands of evergreens) for miles. It was just beautiful up there, and I had some interesting wildlife moments. Tons more birds, for starters. Then I heard a snap or crash and in the distance between the trees saw something large and brown running down the hill. It was either a deer, elk, or bear—all of which had left tracks on the trail at some point—but it was clearly aware of me long before I was aware of it. Later on, a hummingbird came out of nowhere and arrowed towards me. I thought it was going to pass over my head but it stopped, going sixty to zero, about two feet in front of my face, and stared at me, flaring its tail. Then it zipped away. For the Aztecs, hummingbirds and warriors were connected, and this makes total sense.

The aspen trees were heavily marked, and most of those markings were so old they were no longer legible. I get the sense that decades ago, this trail saw heavier use than it did today. I’m not keen on people carving their names into trees, but it is pretty impressive how old some of these trees are!

I kept going gradually up, passing the turnoff for the Lower Ryman trail, and then there was another, shorter section of steep climbing. More of the surrounding ridges and mountains came into view—off to the south, I could even see Dibe’Nitsaa (aka Mt. Hesperus), which is a few miles away from my last campsite north of Mancos.

Then I came to the next obstacle:

There was snow covering the trail. I thought, if it’s like this the whole way, I won’t be able to slog through it all. I might have to turn back. Fortunately, the snow was just a few patches, 10-20-30 feet long, and it was still frozen solid enough at that point that I mostly just walked over it.

Then it all happened very quickly: I got to the forest service road that led to the Highline Trail/Colorado Trail. Then I was at the Hermosa Creek Wilderness boundary!

I know I said that I liked to walk about a mile past the boundary. But the trail here never actually crosses it, and it was a fairly long hike to even reach the boundary. So in this case I was content with just walking around the sign.

But the big thing happening here was the views.

Enhance!

I mean, why? Why is it like this??

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

[inward shouting of incomprehension and delight]

But because language gives us a tool to make sense of things, I can say that part of what boggles me about a mountain range like this one is that there’s both incredible scope and incredible intricacy. Like nature should be exhausted after making *one* mountain that complex and that huge, but there’s another and another and another and…

And there’s also the time scale: the knowledge that in the deep past, if you could sit where I was sitting and watch that specific sector of the horizon for ten years, twenty, a whole lifetime, probably nothing visibly dramatic would happen. And yet, the drama! It looks like they just popped out of the ground last week, all crowding together in their eagerness to start being mountains and do an EMPHATICALLY good job of it.

And because one way we engage with mystery is to make maps, and measure things, and give the mountains names, even when there are so many and they are so big, I can tell you that the mountain range in the distance was about 20 miles from where I was sitting, that on the map it’s called the Needles range, and that these are some big honking mountains.

Even though I could’ve stayed there for hours, after about 45 minutes of sitting and looking and eating a couple of tortillas with peanut butter, I had to start back. I picked up a couple pieces of litter (yes, even all the way up there), tried talking to a raven, and it was literally all downhill from there.

Also literally, it was a very enjoyable walk downhill. I did encounter a few obstacles:

The snow had softened, so it didn’t hold my weight so well and I postholed through it thigh-deep a few times. Totally worth it.

I slipped crossing a tiny stream and landed on my ass in the San Juan mud. Also totally worth it.

Going down the steep sections of the trail was trickier and more dangerous than going up, and my feet went out from under me once or twice. Fortunately I didn’t hurt myself, and still totally worth it.

I’m a slow hiker, I stop often to stare at things, and I take long breaks, so about 12 hours after I left the van, I came back to it tired, hungry, muddy, exhilarated, and content.

So that’s how I hiked into my seventh Colorado wilderness. Here’s to 37 more.