Trash (or, the 13-day, 485-mile journey of three corroded AA batteries)

December 17

I’m looking for a pencil in the zip-top tote bag where I keep my important paperwork and office supplies. I don’t find a pencil, but I do find three AA batteries with an expiration date of 2018. All three of them are corroded, and two are bulging slightly.

I put the batteries in a plastic grocery bag and tie the top. I know that battery acid is Bad For You, but I’m unclear on how it works. Do batteries go bad like spinach, where one day you’ll notice a greenish liquid collecting in the bottom of the bag? Or is it not even a liquid at all, but more of a gel or goo? I imagine it leaking out onto the floor where it will burn the dog’s paws.

I tuck the bag on the floor behind the passenger seat, next to a cardboard box of recyclables. The box once held a pair of wireless headphones that I ordered online and picked up last time I was at my mailing address in Colorado. Now it holds a plastic container from the poke bowl place, a plastic soda cup from a gas station, glass jars, a few energy drink and beer cans, and a sheaf of junk mail.

When I’m near a friend’s or family member’s house, getting rid of my normal trash and recycling is easy—I just ask permission to use their trash can and recycling bin. But when I’m not visiting someone at their home, it can get tricky. Public parks have trash cans, but they generally have holes or baffles to limit what can be stuffed in there—and my four-gallon trash bags won’t fit without a conspicuous struggle. Alley dumpsters are convenient in large cities, but they don’t exist in the smaller towns where I spend the most time. And just as one cannot simply walk into Mordor, one cannot simply throw a trash bag into a private business’s dumpster. They’re usually locked, and they sometimes have “NO DUMPING” signs, or signs announcing the presence of video cameras. Sometimes big-box stores have trash cans in the parking lot, but not always. It kind of burns when I have to shop at Walmart, and I unpack my groceries and put them away while parked in the Walmart lot, but I have to drive elsewhere to throw away the packaging.

Far more often than I like, I’ve shoved a full trash bag into the tissue-box-sized hole in the top of a gas station trash can, furtively glancing around to make sure that no one is watching. I feel bad for the gas station employees: I assume that the presence of vanlifers and RV people mean that the employees have to empty the trash cans more often, adding annoyance and stress for people who don’t get paid enough as is.

I’d be willing to drive my trash and recycling to an actual dump. But those places almost always either charge fees that are steep by my standards, are limited to county residents, or both. The county where I legally reside (Jefferson County, Colorado) charges at least $40 to dump anything at the landfill. The landfill in the county where I grew up (Anne Arundel, Maryland) is free of charge but only for county residents. There are only two places that I know of where, as a non-local, you can drive in for free and toss a single bag of trash: Pahrump, Nevada, and Quartzsite, Arizona. Both of these areas have huge winter snowbird populations.

But today I am in Taos, New Mexico. There aren’t many winter snowbirds, but with a population of almost 7,000, it’s a pretty sizable town for the region. And it’s kind of a hippie town, with shops that sell healing crystals, an organic honey store, and earthship homes made out of adobe and old tires. I’m hopeful to find someplace where I can recycle these stupid batteries sometime in the next few busy days.

December 18

I’ve been running a ton of errands, and I have to step around the plastic bag of batteries every time I get in or out of the van. In a moment of downtime, I type “battery recycling” into Google Maps.

It returns a solid handful of places to buy batteries, both automotive and household: auto parts stores, hardware stores. There’s also the municipal landfill, so I click on that. The landfill is open only to county residents, and it doesn’t say anything about recycling batteries.

Time for a web search instead. I get a hit, right at the top of the page: the Taos County website has a page titled “Batteries”! I click, and I learn that the county recycles vehicle batteries and lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, but not alkaline batteries, and not batteries that are leaking.

For my leaking alkaline batteries, it tells me:

“For single-use batteries or leaking batteries: It is currently legal, though not ideal, to dispose of alkaline batteries in the trash. Some single-use batteries, such as coin or button cell, contain lithium primary and should be recycled if possible. This can be done through Call2Recycle, an industry-sponsored non-profit battery recycler. It accepts all types of batteries, including single-use batteries and damaged batteries (in special containers). It does this with prepaid mailers, which is your only cost. These range from small boxes to drums. See https://www.call2recycle.org/store/.”

The “legal, though not ideal” line feels like a dig. I want to do the ideal thing! And sure, ordering a prepaid mailer would be a fine solution if I had a fixed address, but I don’t.

It’s estimated that there are over three million people in the U.S. living in vehicles. That’s almost 1% of the population that has a hard time disposing of their trash and recycling in the “ideal” way. I imagine this problem goes beyond nomads, though. What about people whose parents aren’t nearby and are in declining health? If a parent moves into assisted living or dies, the grown child needs to come and take care of all their parent’s stuff. There’s usually a ticking clock: the grown child can only take a week off from work, or the home needs to be ready for the next renters or put up for sale ASAP. This person is probably very stressed and sad and and moving at top speed to get everything done. They aren’t going to have the bandwidth to plan ahead and make sure they order the prepaid battery mailer early in the cleanout process so they can be sure it will arrive in time. They have bigger things to worry about: furniture that family members don’t want, sentimental items that someone might want, closets full of clothes, filing cabinets full of documents. Those batteries are going in the trash.

The ticking clock has also been a factor for basically everyone I know who has moved from one cheap rental apartment to another. To avoid paying rent for someplace where you’re not living, you try and get your move-in date and your move-out date as close together as possible and condense your move into a week or less. You drive carloads of stuff across town to your new place in the evenings after work, and you stay up late packing and cleaning. Here again, there’s no time to wait a week for a battery mailer.

I used to wonder about those people who throw a whole mattress into a wooded ravine or dump an old mini-fridge and a set of beat-up chairs in the desert. On some level I thought they must be amoral and depraved. How could such monsters walk among us looking like normal people? But now I see more desperation than depravity.

I can borrow my cousin’s truck to help move the furniture, but I have to bring it back on Sunday night.

The landlord says mom’s place needs to be empty by the 31st or we’ll have to pay for another month.

At least I have the luxury of time, with my one little box and one little bag. Moving on, I see another promising-looking website, therecycleguide.org. “We partner with local recycling centers,” it says, and there’s a phone number. But the information is purely generic, about different categories of objects that *theoretically* could be recycled, like computers, cell phones, TVs. No information about what these local recycling centers actually are, what they take. It’s implied that this service, whatever it is, probably charges a fee, but there’s no information about that either. I guess that this website is a scam designed to get people to call the number. For this to be a worthwhile scam, a lot of people must be Googling, “how to recycle [ insert object here ] in [ insert town here ].”

A friend who once worked for a city sheriff’s department told me that sometimes people would run an electronics recycling hustle. They’d get a cheap old utility trailer on craigslist, park it somewhere they wouldn’t be bothered, and advertise that they were doing electronic waste collection. Residents could drop off their hard-to-dispose-of old TV sets for only $20. Once the trailer was full, the “recyclers” would drive away with a fistful of twenties and leave the loaded trailer behind. The sheriff’s department was ultimately responsible for the cleanup.

The kicker is that those TVs actually did end up being properly recycled—although it ended up involving the use of law enforcement resources and probably substantial cost.

I skim through the rest of the search results page, which all look like either a) legit but high-cost paid services, b) more scams, or c) AI-generated slop. I’m not going to be able to recycle these batteries in Taos. But I’m visiting a friend in Santa Fe in a couple of days. It’s a bigger town, so maybe I’ll have better luck.

December 21

As it turns out, I did not have time during my Santa Fe visit to find a place for the batteries. My friend said that I was welcome to use her recycling bin, although for some reason the city didn’t pick up glass. To get rid of my whole box of recyclables, I could drive to the free transfer station a couple miles away.

I gladly did this and was happy to be rid of the box. Now I’m driving north, planning to get to metro Denver by nighttime. The dog has a vet appointment the next morning, and then it’s Holiday Time. My parents are flying in from Maryland, hosted by my brother and sister-in-law, who live in the south suburbs. There are dinner plans, brunch plans, Christmas morning plans. I still need to buy presents for my nephews. There are some friends I’d like to see. The batteries are still in the grocery bag behind the passenger seat where I have to step around them while getting in or out of the van.

In Trinidad, Colorado, I pull into a gas station. Almost every pump is occupied. People are on the move today, making the trek north or south on I-25 to get wherever they’re going for Christmas.

The gas station is large and newish, the parking lot not yet coated with drips of oil and splatters of grime. It seems pretty well maintained. The buckets of windshield washer fluid are full, and the trash cans are not overflowing. But next to a couple of the trash cans are empty plastic jugs that once held DEF, diesel exhaust fluid. They rattle in the stiff wind. A good gust will whip them across the parking lot and out onto the plains unless one of the underpaid employees comes out of the busy convenience store and picks it up.

DEF is part of modern emission-reduction systems for diesel vehicles. It’s been around since about 2010 for heavy-duty diesel trucks, and it was phased in for lighter-duty vehicles like pickup trucks and vans. DEF itself is a good thing, since it reduces the most harmful elements of diesel exhaust, but it has also generated a new abundance of plastic trash. The vehicles that need it need a lot of it: a diesel Mercedes Sprinter, the archetypal Instagram Vanlife Van, needs almost a gallon every 200 miles. Some fancy gas stations have pumps for DEF, a small nozzle right next to the nozzle for diesel fuel, but most don’t. Mostly, it’s sold in 2.5 gallon plastic jugs. I have never seen a gas station trash can big enough for these jugs to fit into. And I have never seen a recycling bin at a gas station, period.

A driver traveling from Albuquerque to Denver for the holidays would probably consume one jug of DEF en route. Ideally, they would place it in the back seat until they reach their destination, then put it in the recycling bin at grandma’s house. (I hope those jugs are recyclable, but I’m actually not sure.)

But say you have your partner, two children, a dog, four humans’ luggage, the dog’s food, and presents for your nieces and nephews and grandma all packed into your quad-cab pickup. You are not going to ask your oldest child to hold the empty DEF jug on their lap for the next 260 miles, especially since who knows what is in that stuff and your youngest child still touches everything and then puts their hands in their mouth. You are going to put the empty DEF jug next to the trash can and hope that one of the underpaid employees will pick it up before it blows away.

From a resource and environmental perspective, this is definitely a problem. People have to buy this stuff in containers, and there’s no way to dispose of the containers at the point of use. But it’s not a problem from the perspective of the manufacturer or vendor. You bought the container of stuff; it’s your problem now. If you want it not to blow onto the plains and spend the next thousand years breaking down into microplastics, then you figure it out.

Sometimes when I’m driving, I’ll think of all these great businesses that I would start if only I had the actual skill, knowledge, and money to run them. Some recent ones include:

An iodine-free dairy farm that makes cheese for people with thyroid cancer.

A dating app with no swiping and no algorithms, just a text search so you can find people who share your favorite authors or weird interests.

But a surprising amount of my ideas kind of relate to trash:

A company that builds modular homes out of decommissioned fiberglass windmill blades.

Or the one that uses recycled aluminum cans to make packaging for other foods: peanuts, candy, chips. This company would be called Yes We Can.

Or the one that builds camera, computer, and conveyor-belt systems to sort trash. The software could be trained to recognize common shapes and materials, then use railroad-track-type switches to shunt each item into the appropriate branching conveyor belt for additional sorting and recycling.

Of course, in my trash fantasies, I don’t have to worry about making any of these things commercially viable. In my fantasy world, taxes on large-scale food producers subsidize nationwide programs for the collection and recycling of food packaging. Gas stations that sell DEF also have recycling bins for the jugs, and that plastic recycling is picked up by local municipalities because recycling whenever and whatever possible is viewed as an essential civic responsibility, kind of like wastewater treatment plants.

In the real world, the three corroded AA batteries are still behind the passenger seat. On a straight and uncrowded stretch of I-25, I try a Google search again, and again I see plenty of places to buy batteries but nowhere “ideal” to throw them out.

December 30

Christmas has come and gone. At my brother’s house, the trash cans and recycling bins have filled, were emptied, and are filling again. I have left my brother’s house in the suburbs and moved on to Denver. The batteries have remained in the grocery bag behind the passenger seat.

A few months ago, I helped a friend clean out her garage. This is the same friend who once worked for the sheriff’s department and who told me about the fake electronics recycling hustle. She had some of the usual accumulated debris of life in a sizable old house: cans of paint, half-full containers of old household chemicals like paint stripper and old antifreeze and oven cleaner, dead fluorescent light bulbs, broken remote controls and obsolete electronic cables. My friend is a highly ethical person who wanted to recycle whatever she could and dispose of anything un-recyclable or toxic responsibly. We drove the paint to a paint store that would take it. We took the electronics to a computer shop 25 minutes away that said, front and center on their website, that they take in old computers, cables, batteries, and almost everything except old tube TVs, for free.

But the hazardous chemicals were tough. We found services that would take it for a steep fee. Her county usually offered free hazardous household chemical pickup, but the website said that the city had exceeded its 2025 toxic waste pickup budget in June, so no more pickup until 2026. My county of official residence could take it at a special recycling center—but the center is by appointment only, and the only open dates were weeks away. I was scheduled to leave town long before that.

The rows of bottles took up valuable real estate on the garage floor. I got so frustrated that I suggested that maybe we should just throw that stuff in the trash. Almost everyone does throw this kind of stuff in the trash. But my friend, to her credit, said she would wait for the new year.

I remember the computer shop that took my friend’s old cables and remote controls. In a break in between errands and work, I drive down there. At this point, I have more electronic waste to get rid of because I accidentally snapped the data cable for my satellite dish.

It’s a 14-mile round trip from central Denver to the computer shop and back. I finally disposed of the batteries in the ideal way, but I burned a gallon of gas to do it. Between carbon emissions and battery acid leaking into the landfill, I don’t know which side of the equation is heavier.

Highlights

Having grown up in Maryland, I thought I knew mosquitoes. I thought I understood what it was like to be someplace with bad mosquitoes.

But Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has made me aware of the limitations of my understanding. These mosquitoes are at a whole different level.

I came to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula during peak mosquito season in order to get away from the heat dome that settled over most of the Midwest and Northeast. Northern Michigan doesn’t get one up out of the heat as well as the Rockies, but it’s definitely better than where I was a couple of weeks ago (southern Ohio).

It’s been a while since my last update. Some of that has to do with the fact that the way I do nomadic life, most of it is pretty boring. I work. I do laundry. I buy groceries and then eat them. I spend a lot of time in places that don’t lend themselves readily to travel blog fodder: metro Denver, Albuquerque, the Maryland suburbs, Dayton. I’ve spent a lot of time in family members’ and friends’ driveways, or parked on the street in front of their homes.

Though for me, this is actually one of the great advantages of nomadic life. I was able to help one friend relocate, join another on road-trip vacations, and spend time with my parents. Lend a hand with yardwork and basement cleanouts. My network of friends and family is pretty geographically scattered, but in some ways I feel more connected to people than I did at other times when I was more tied to one place.

But there have been some highlights, and I’ll tell you about them.

One big highlight of the last year is that I have taken on a part-time passenger. In fact he’s in the photo above.

** Enhance! **

This is Puck. He is a four-year-old hound and possibly border collie mix. And I love him so much.

(Here is a better photo.)

Puck was adopted as a puppy by my friend Ron in 2021. He was a Hurricane Ida rescue from Louisiana, and even as a tiny baby his wonderful personality was clear—curious, sweet, goofy, and eager to please.

However, it was also evident pretty early on that Puck is not a low-maintenance dog—he does best with a couple of hours of exercise a day. This was fine until Ron started grad school last fall and found that doing an intense master’s degree program plus an assistantship plus walking the neighborhood 12 or 14 hours a week was a lot. Meanwhile, I’d known and loved Puck since his adolescence, he’d stayed with me in the van a few times before and seemed to enjoy it, and I like to walk a lot anyway. So I figured I could take him on board when Ron’s workload is the heaviest.

Puck was with me for a chunk of this past fall, some of the winter and early spring, and he’s here with me now, sleeping with his head on my shin, snoring lightly and chewing something in his dreams. (Possibly he’s recovered the dead fish that he found on the shore of Lake Michigan the other day, the one that I made him drop even though it was obviously delicious and would have been a super healthy meal.)

It’s been delightful to have him with me. I’ve loved showing him some of my favorite places and discovering new ones together. It’s also introduced a new set of challenges. (e.g., what do you do when your vehicle is in the shop, and the vehicle is also your house, and the vehicle is also the dog’s house, and it’s cold and super windy out?)

Those challenges, however, are for another post. Right now I want to list some of my recent favorite discoveries, in terms of places I’ve been and things I’ve seen.

The southern Appalachians

A couple of years ago, I went through north Georgia and the western corner of North Carolina. I think this area is typically a summer or fall destination, though I passed through in early spring and I really liked the cool but not freezing weather and nearly-empty hiking trails.

Highlights included Clayton, GA (a cute small town with some good hiking nearby), the Linville Gorge, and the area near Robbinsville. That area is home to the Joyce Kilmer forest (which is one of very few preserved stands of old-growth woods; I loved the huge tulip poplars) and a few amazing dispersed sites by a lake (pictured). I only spent a couple of weeks in this area, but it’s one that I hope to revisit.

Hawaii (Oahu)

My three cousins grew up in Hawaii, and one of them got married there recently. It was great to see family (both from Hawaii and the mainland) and explore the island with them. I extended my stay for a week or so after the festivities wrapped up: I brought my backpacking tent, rented a car, and did as much snorkeling as I could while also having to work. This was in August, and August in Hawaii is very hot; fortunately, the car I rented happened to be a hybrid, so I could sit in the car to run the air conditioning and work while charging my laptop. Camping in Hawaii is very different than on the mainland, which could also be its own blog post. (I booked a state park campsite on Statehood Day and it was basically tantamount to sleeping on the ground in the middle of an all-night rave.)

This was worth all the sweat and more, because the snorkeling was incredible. My favorite spot was Oahu’s north shore, specifically a spot called Shark Cove. I spent hours there, surrounded by fish of all kinds and colors, some of whom were new to me. Favorite sightings included the colorful and wonderfully parallelogram-shaped humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa (the state fish of Hawaii), a long-tailed spotted eagle ray that came sweeping in from the ocean like a ghost or an angel, and two sea turtles that came to hover in a specific area and were cleaned by two different types of fish in a two-stage system: first the bigger fish for the power clean, then the smaller ones for detailing.

Hawaii is also delicious, and while I tried to stick to a budget diet of peanut butter sandwiches and oatmeal, I could not resist the poke bowls, which are so good.

Albuquerque

Albuquerque is the Baltimore of the southwest.

Sounds weird, perhaps, but consider that the following apply to both cities:

Bad reputation that is to some extent driven by a famous TV show (The Wire, Breaking Bad)…

… and to some extent earned.

Large-scale, city-defining natural feature (the Chesapeake Bay, the Sandia).

Really good regional cuisine.

Often outshone by a nearby city that is more picturesque, “historic,” and touristy (Annapolis, Santa Fe), which hosts a campus of St. John’s College.

Cost of living is more affordable than that nearby picturesque touristy city, drawing working artists.

Climate mostly great but terrible in the summer.

Generally underrated.

Quartzsite, AZ (my first vehicle nomad meetup)

So if you’ve ever seen the movie Nomadland, with Frances McDormand, you may remember the part where she drives to the desert and meets a bunch of other vehicle nomads, and they have campfires and informational talks and learn how to fix a flat tire? That’s a real thing, the Rubber Tramp Rendezvous or RTR, and it still happens every year in southwestern Arizona.

I went in January 2024. As a strong introvert (84% “I” on the Myers-Briggs), it was a little overwhelming, but it was also great. I met a couple of other women there who I still stay in touch with. It’s really nice to know a few other people out there on the road, to check in with each other every once in a while and share tips and places to go, to gripe and commiserate, even if you’re many miles apart.

The RTR was also perhaps the first time I ever struggled to find my van in a parking lot.

Arizona, in general

I’ve passed through Arizona a few times, and there are a few areas that I’d really like to explore more at some point.

Sky Islands — This is a name for a set of mountains in the far south of the state, kind of by Tucson. I think they get their name because although surrounded by desert, each peak has a rich, forested ecosystem, which you see as you climb up and up. There are ocelots in these mountains; years ago, there was a jaguar.

Also in this area: the Paton Center for Hummingbirds. Decades ago this was just someone’s house with a big yard, but it also happened to be a migratory bird and hummingbird hotspot. the owners donated it to a nonprofit, and now it’s an internationally known bird nerd destination. On a twenty-degree morning, I came shortly after the staff had put warmed nectar in the hummingbird feeders and watched multiple species zip in to warm up.

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed spending a few days in Sedona. It’s in a beautiful spot, with these amazing mesas and butes, swirls and whorls and blobs of red sandstone, pines and flowers and Arizona sycamores; it’s also heavily developed, monitored, trafficked, and touristed. I was thinking that for me, the latter would overwhelm the former, but it didn’t. The beauty of the place is that unique.

There is one forest service road that is famous/infamous in the van life and nomadic communities: it was once one of the most sought-after destinations for vehicle camping, it got internet-famous, it got trashed, and now it’s closed to dispersed camping. Campers are still allowed, but limited to a handful of designated campgrounds that are basically just parking lots.

I did drive down this road and stay one night; it’s gorgeous, and it was a great walk in the morning. However, it’s a long drive to just cross your fingers and hope you find one of these hotly contested sites. I stayed further from the popular areas, either at a rest area just outside of town or at a dispersed camping area between Sedona and Flagstaff, and that was less stressful.

The hiking trails too can get overrun and crowded and thoroughly un-magical in the middle of the day. So what I ended up doing is going very very early—like butt crack o’dawn—or late, after people have headed to dinner.

And while it’d be tough to live here because the town is clinging to the side of a mountain and there’s no real place for a nice long walk, I enjoy stopping in Jerome. This one-time mining town south of Sedona has a lot of ghost stories, and it really leans into that. There’s a creepy old jail that is sliding down the hill, a restaurant called the Haunted Hamburger, and for some reason, several pinup/rockabilly clothing boutiques. I had the chance to walk through sometime in October and it did not disappoint.

Also in Arizona, I crossed the border to Los Algodones, Mexico to get dental work done. For twenty years, I’d been hoping to be able to save up enough money to get an implant to replace a tooth I had pulled at age 24. I was quoted approximately $7500 for this in Maryland and finally accepted I could never afford it unless I went to a different country. I had it done in Mexico for $2000, and so far, the implant seems to be holding up. This was prior to the 2024 elections, so I’m not sure if the increased tension and new administration’s policies changed the logistics of border crossing, the town’s economy, people’s livelihoods, or the general vibe of an international dentist visit, but at the time I went, it wasn’t difficult or scary, and it was a good experience overall.

Rio Chama Canyon

This isn’t a place that’s new to me, but I’ll end with the Rio Chama Canyon in New Mexico, which is one of my favorite places in the world and one I’ve been lucky to visit multiple times. Sometimes by myself…

… and sometimes with a friend.

My favorite campsite of late has been near the mouth of the canyon, in this nook of rocks. But if you keep driving this (sometimes a bit rough) gravel road for 13 miles up to where it ends, there’s a monastery that’s one of the most peaceful and beautiful places I’ve ever visited. I’m not sure whether the whole canyon feels like a good and safe and sacred place because of the monastery, or whether they put the monastery there because the canyon feels like a good and safe and sacred place, or whether it’s all just me and my associations. But in addition to returning there physically/literally, this is a place I go back to in my head sometimes, and it makes me feel both protected and free.

These are some dark times, and I’m wishing both protection and freedom for all of you, and your families and communities. (And if you’re ever in New Mexico, or in any of these places I’ve written about, I’m happy to privately share the coordinates for my favorite campsites.)

What I Did This Summer (and so far this fall)

Hello from downtown Mancos, Colorado, where a large crow (or maybe it’s a raven, I can’t tell the difference at a glance) is cawing from atop the baseball backstop at the park, the wind is scattering cottonwood leaves, and the windows of the pizza parlor are decorated with large images of anthropomorphized candy corns.

It’s a perfect time to talk about summer.

From late May through mid-August I was in Maryland, and a lot of the time, I was focused on this:

… which was bunion surgery on my left foot. I’d had surgery on my right foot in 2017, which was a bunionectomy plus two osteotomies (cutting bones and putting them back together) plus a plantar plate repair (cutting ligaments and sewing them back together) plus removal of a big Morton’s neuroma (a non-cancerous growth on the nerve).

Fortunately, my left foot pre-surgery wasn’t nearly as bad as my right, so a lot less needed to be done to it. But it was also crazy how less painful and debilitating of an experience it was. I had surgery in mid-July, and 37 days later, I was back in the van and on my way to Maine, where I was able to walk a mile or two on trails and gravelly sandbars. I’m pretty sure that 37 days after my 2017 surgery, I was still limping around in a protective boot, unable to go anywhere except my desk job and physical therapy.

The thing was that this year’s surgery was not only to correct a less severe issue, but it was a whole different type of surgery, involving three tiny incisions rather than one big one. In a bunionectomy, the bone is cut apart and then screwed back together in a better position. Even though the screws in my left foot are actually much bigger than the ones in my right (think deck screws vs. laptop screws), the pain in my left foot was only a fraction of the pain in my right… like 1/10th.

This time I also took advantage of my one-week post-surgery hydrocodone prescription to quit all caffeine (I’d been drinking a LOT of tea) and start a new diet — and I think that quitting caffeine may have been a more painful experience than the foot surgery, overall.

Coco, my parents’ cat, was very helpful in the recovery process. She came to my parents last winter but had spent most of her life in a barn, where she’d somehow managed to survive despite being totally deaf and having bad eyesight. She was an older cat, though no one knows how old. This summer she started weakening quickly, and she died in September. She is missed, but she seemed to enjoy the ten or so months at the end of her life that she got to spend in a safe, comfortable place with lots of affection.

I stayed in my parents’ guest room until mid-August because a) I had some surgery follow-ups and physical therapy, so I needed to stay in the area and b) it was absolutely disgusting outside and way too hot for me in the van, even at night.

Then in mid-August, it was time to head north.

This doesn’t look like much, but it’s actually the NYC skyline just before sunrise.

On this northern trip, I was accompanying my friends Melissa and Dave and their two kids. When the kids were young, Melissa and Dave decided to visit all the country’s national parks, and they’ve made impressive headway, including some more remote spots like the Dry Tortugas and less impressive-sounding ones like Cuyahoga Falls. Just recently, they got their own campervan. (I am thrilled about this, and also please note and consider that I want all my friends and people I like to get livable vehicles so we can hang out in the woods/mountains/desert/park/wherever.)

I stopped to do some work in a small city in the Hudson Valley (which was really appealing and which I’ll have to check out later), then drove up to our rendezvous point in southern Vermont.

First time I’ve ever seen a porcupine in the wild — it was actually in an old graveyard inside the national forest!

Once Melissa and Dave and their family made it up north, we explored two sets of mountains: Vermont’s Green and New Hampshire’s White. The Green are softer, with denser woods; the White are more rocky and rugged, with some more dramatic dimensions and geology. I’d love to go back to the White Mountains just for hiking at some point.

But one of my biggest motives for writing this blog post is: I need you to know that off Route 11 in rural southern Vermont, there is a hair salon. The name of the hair salon is I’ll Cut You.

That is all.

We drove to Acadia National Park in Maine. Because I’m a lucky asshole, I’d been there twice before. Melissa and Dave had been there once before, but it was the first time for the kids.

There was a snail race.

And we did Maine Things, like eat seafood at a restaurant on a pier.

Sometimes people are surprised when I tell them I don’t go to national parks very often. They’re amazing places, but they’re generally not super livable for nomadic folks. Cell phone/data coverage for work can be nonexistent or spotty. The campgrounds are often full, they can feel quite busy compared to a middle-of-nowhere dispersed spot in a national forest, and they require reservations and advance planning. Plus, they’re expensive by my standards ($30+ per night), and then there’s a park entrance fee on top of that. (This year, since I knew I was going to several national parks, I got the annual pass to cover entrance fees, which at $80 is a pretty good deal — and the same price, I think, as when I took my first cross-country road trip in 2002!)

So when I do go to a national park, it definitely feels like I’m on vacation. And I really liked the campground at Acadia, which felt a little more spacious and relaxed despite being absolutely huge with hundreds of spots. But probably the best thing about staying inside the national park is that it gives you night access. Melissa came up with a brilliant idea for seeing Thunder Hole, a narrow crevice in the rocks where the waves go BOOM about an hour before high tide if the wind and waves are intense enough. Thunder Hole is wonderful but it’s one of the most heavily visited spots in the park, with crowds of people jostling around so you can barely see the Thunder Hole itself. Often, during the time/tide window when the Thunder Hole might be thundering, the parking lot is full.

So we just went at night! For something like Thunder Hole, where so much of the experience is sensory but not necessarily visual, this was awesome. We turned our headlamps off to stand there with the waves and the dark for a minute, then turned them on to spotlight Thunder Hole as the water sucked back and crashed over the rocks. And there was absolutely no one else there — no pressure to move over, move on.

It does sadden me to report that one of my favorite ever road signs, the one that said “THUNDER HOLE RESTROOMS,” has been removed. It has been replaced with a sign that simply has the restroom graphic and is thus much less satisfying to make stupid jokes about. R.I.P., Thunder Hole Restrooms sign.

Normally, on a trip like this, I would’ve wanted to do a Big Hike, but since my foot still wasn’t ready for that, we went sea kayaking instead. This was wonderful. We didn’t go super far, only a few miles, but I really loved being out there on a beautiful day, especially when we got into the channel between the islands, where there were some gentle but large swells. I’ve paddled in Chesapeake Bay rivers when they were kind of choppy, but never in any actual waves, and I liked the feeling of it.

On our last morning in the park, we drove up Cadillac Mountain to watch the sun rise. Melissa and Dave had to go back to Maryland so the kids could start school the following week, but I was able to stay in Maine for a couple more days. So I drove up the coast to Machias. This was the farthest north I’ve ever been in Maine, and I really liked the area. It’s less trafficky, less busy, but the coast is still absolutely beautiful. Plus the town of Machias itself seems pretty nomad-friendly, with two town-owned parking lots that are set next to a lovely river and where overnight parking is explicitly allowed. I’d taken time off of work for the Acadia trip, so in Machias I did just work a lot, but I’d love to revisit this area and stay longer.

This is Jasper Beach. It’s known for its pebbles that make a wonderful sizzling noise as the waves roll in and recede. These pebbles are not actually jasper, but rhyolite.

Rock lobster!

On my last morning in Machias I went to this coastal preserve on the beach to do some work. When I got there, it was low tide, and folks were digging for clams on the exposed muddy flats, hundreds of feet below the high tide line. After a couple hours, it was time for me to go. I’d driven onto the beach, just below the highest high-tide line, on what looked like a strip of well-used, hard-packed sand and gravel. I’d had no problems getting onto the beach, but instead of putting the van in reverse for a hundred or so feet, I went to turn around — and backed off the hard-packed strip and into sandy gravel that was much softer than it looked.

Yes, I got my dumb ass stuck. Very stuck.

This was quite stressful since by this time the tide was coming in. Of course it was a Sunday and all the towing places were closed. My insurance’s roadside assistance was sending someone, but they were about an hour and a half away, maybe two.

There were two lines of seaweed on the shore, and I was in between them. A couple passing locals told me that the highest line represented a storm tide, and I would probably be out of the reach of the normal high tide, but this still did not feel reassuring. I tried to dig myself out, and I used the traction strips that I’d ordered for just this situation… but each time I tried to get out, the van just went in deeper. I couldn’t quite see what was going underneath, but I suspected the rear differential and/or the spare tire were actually resting on the ground, which would be… very not good.

Despite Machias’s frequent appearances in Stephen King novels, where the scariest thing is not actually the monster but the people, my experience with the people of Machias was bizarrely positive. Everyone who passed by seemed to offer help of some kind — they’d call their husband, who was probably out in the garden right now, but if he did answer the phone, might know someone who could help. Or they could call their friend not too far away who had a farm tractor, and maybe the tractor could lift the van out of its hole. With the tide rising quickly and the tow company still hours away, I did take someone up on their offer — a young couple who’d come to the beach to walk their dogs. The guy’s father lived a few minutes up the road and had a big truck.

Even with the big truck, it took a while (and a couple of calls to the guy’s high school buddy’s dad Timmy, who owned a towing company) to figure out how to get me out. There actually aren’t any good points on the front end of my van to attach a tow hook (which seems like a big oversight), and I was worried that if they tried to pull me out backwards, it would just pull the rear axle/spare tire/exhaust system/bumper into the gravel. Plus if that towing attempt failed, it would put me much closer to the incoming water.

Finally I got desperate enough to say OK to being pulled out backwards. And… it worked. There were a couple of scuff marks on the rear differential and a bunch on the spare tire, but the van seemed undamaged. There were high fives all around, and even though I will never willingly repeat this experience, I’ve gotta say that the adrenaline rush of having your home threatened by an inexorably incoming tide, and then getting away from it, is really something else.

Once I was safely above the highest high tide line, my rescuers and I (native Mainers whose names are Riley and Joelle; Riley is an actual lobster fisherman) stood around and chatted for a while. Then I filled in the big holes I’d made in the beach and was on my way. I plan never to drive onto a beach again.

This pic was taken from about the same spot as the earlier photo on the beach; note how much closer the water is!

I had a doctor’s appointment in Maryland and a bunch of work to do, so I made my way south over two days: the first evening I stopped at my friend Sarah’s in the Finger Lakes region of New York, and the next at my friend Sasha’s in South Jersey. I wish I could’ve stayed longer in both cases, but it was great to be able to catch up a little bit.

I spent another week in Maryland, full of logistics, medical appointments, and way too much dental work. (One of my old root canals failed, which cost over $2300 to fix and my dental insurance covered none of it. The fact that dental work is so expensive and that teeth are considered luxury bones that are not covered by insurance in any meaningful way is very upsetting to me, and I think that the next time I need a root canal or re-root canal or new crown or anything like that, I’ll just have the tooth pulled and then go to Mexico and get it replaced with an implant.)

It was a stressful week, but I did get to do some Maryland Things: make air fryer crab cakes, hang out in my friend Meg’s hot tub/on her porch, and go paddling with my mom on the bay.

In early September, I got on the road again, this time headed south. I met up with my friend Ron in South Carolina and we visited Mepkin Abbey, a Trappist monastery.

Ron stayed at the abbey for the full residential retreat experience, while I camped nearby with his dog Puck and just came to the monastery in the daytime.

The live oaks at this monastery are some of the most incredible trees I have ever seen.

After Mepkin, Ron headed back south to Florida and I turned west, where I got to spend a couple nights with my brother and his family at Lake Oconee in north Georgia and at their home in Atlanta.

Then, I headed west…

And now I’m in the San Juans, in southwestern Colorado. I missed being out here this summer, and it’s been a busy October so far, with tons of work — but I’m glad I’ve gotten to spend at least a couple weeks out here before it gets too cold. Already I’ve had one below-freezing night, up at about 9,200 feet in the West Dolores River valley.

But it was absolutely worth getting up in the cold to be able to go out hiking and watch the sun hit the peaks.

And the trees… I just can’t even deal with it.

How is this real???

1917, 1947, or 1941?

And yes, my phone is about 90% photos of trees and mountains.

I need to head back into the woods now, but sometime soon I hope to post about staying warm when living in a van — a topic that I’ll need to give more thought to in just the next couple of weeks!

The Island

In the river by my parents’ house in Maryland there is an island. It’s not big, only about fifteen hundred feet long and a couple hundred feet wide at its widest point. But it’s dramatic: on its south side, sandy cliffs rise out of the water. It’s topped with tall, twisted loblolly pines and tangles of climbing vegetation. On the north side, there’s a long, sandy beach where the water deepens gradually, a perfect swimming spot.

Growing up, I knew this island as a wild place. My parents would take me and my brothers there and beach the boat, and when each of us got old enough, we were allowed to wander around the island on our own. There was only one way up off the beach to the island’s raised interior: a scramble up a steep, sandy, eroding hill. Once I was up there, I felt as if I’d left the world I knew behind and stepped into a much more expansive one. This could be what it looked like just after the dinosaurs went extinct: golden light slanting through pines, cicadas buzzing in the jungly vines, and ospreys calling — which basically sound like longing made audible. I spent hours up there, standing just far enough back from/close enough to the cliff that I felt the exact right amount of danger, or following the trail (there was only one trail, really, on such a narrow island) until I lost it in the vines.

And then a group of other people in bathing suits and flip-flops would tromp past, the adults talking loud and the kids sticky-mouthed, and for a minute it would break my illusion of being the only person for a hundred miles.

Despite feeling so primeval while I was up there, this island, Dobbins Island, was and is totally enmeshed in our human times. It’s been a party spot for well over a century, since the time when the sandbar was still close enough to the river’s surface to drive a horse-drawn carriage from the mainland to the island at low tide. At one point, someone had built a stone house on the island, which lasted for a while and then crumbled away. (One summer, in the most viney part of the island, a friend and I found a round stone cistern set into the ground, with some scummy green water at the bottom, and part of what could be a foundation. We could never find it again.) Just a little before my childhood, the island was apparently an exchange point for cocaine smugglers: the cargo was landed in float planes and transferred to waiting boats. And since my childhood, summer weekends mean that the island’s shallow anchorage is full of boats. People everywhere, with pool floats and super-soakers and coolers full of soda and beer. Sandwiches, boomboxes, cigarettes, sunscreen.

When I was growing up, I understood that the island was owned by a family who had held it for a few generations. There was some kind of complicated legal structure involved, and family members who did not get along. They could, if they wanted to, put up “No Trespassing” signs, or a fence, or houses, at any moment. The only reason I was able to enjoy this place was because the owners lacked the motivation or unity of will to kick people, the public, off of it. By the time I was in middle school, I was aware that the island as I knew it might not last forever.

It lasted through my high school years, and my brothers’. But in the early 2000s it was sold, and soon after, the new owner put up the “No Trespassing” signs. It was rumored that he wanted to build a house.

Each step of the process was marked by some kind of controversy or resistance: people called for the county/the state/a local conservation group to buy it and make it into a park, or better yet, just keep it as it was. At one point, a fence went up to keep boaters off; there was a legal dispute, and the fence was removed.

In most states, including Maryland, the rule is that the public has a right to be on any beach or shoreline as long as they stay below the mean high tide line. Below that line, landowners have no legal right to bar people from beaching a boat, building a sandcastle, or sitting in a chair with their feet in the water. Even if there just so happen to be a few dozen people, or a few dozen boats full of people, or, as reported in 2011, over 800 boats full of people at the annual “bumper bash” party.

About a decade ago, the island’s new owners finally built the house and a long pier. Fortunately and unlike what happened in the case of a smaller island nearby, the owners at least obeyed zoning and environmental restrictions, so from the water, aside from the pier, the island hasn’t changed too much. In the summer, the trees mostly screen the house from view.

I paddled around the island a few weeks ago in a friend’s kayak. Four or five ospreys circled or roosted in the trees, and kingfishers — a beautiful bird I never saw on the river growing up — have dug holes in the cliff to nest in. It’s still beautiful, and there’s still a sense of wildness about it, and also a sense of accessibility — at least below the mean high tide line. It could still be a magical place for a kid, or an adult.

But of course I felt a sense of loss. Without access to the island’s interior — the scramble up the steep hill that marked one’s palms with clay, the breeze coming up from the river — I can’t get inside that wildness, either, not as fully as I once could.

And the time I’ve spent in the west recently heightens that contrast. This spring, I spent a little time in Utah and more time in Colorado, with a trip to Death Valley and Canyonlands national parks in there as well, and these are all places where the dynamics of wild places and public land are very different. There’s public land in the county where I grew up, and some of it is still just trees with crisscrossing trails, but they’re smallish pockets of land, relatively, and the gates close at dark. There’s noplace within a two-hour drive where you could walk for a day without coming to the end of the trail, and of course there’s no public land where I can park my van and stay for free.

I was recently talking to a friend about the difference between wilderness and wildness. Wilderness is pristine, preserved; wildness just hasn’t been touched for a while. It could be an old clear-cut where the trees are growing back — not the irreplaceable old growth, but whatever species are up for the task — or an island with vines growing over the foundations of an old house. Maybe wildness could even be a very overgrown backyard, or any other space where human attention is mostly turned the other way and natural forces are dominant.

Wilderness — like Colorado’s 44 designated wilderness areas that I’m trying to hike — is something I only encountered as an adult. And I love it, obviously. But wildness is what I grew up with. Like the island, or like the woods next to my parents’ house. (This woods, too, is now fenced off and built up with boring and oversized houses, but before that, it was glorious.) These kinds of wild places — the marsh by the road,the yard where saplings grow around the wrecks of old boats and cars — feel charged with a unique kind of energy. They’re scrappy, the natural order fighting hard to stay or to make a comeback. As long as those places last, it feels like they’re getting away with something.

Another thing about wildness: it can be anywhere. Vacant lots, slips of suburbia too boggy or difficult to build on, or next to Cherry Creek in Denver where herons pluck fish out of the water in the shade of an overpass. When I took a train through Eastern Europe in 2006 I saw people picnicking on the slope above the train tracks, and I bet they were there for the wildness.

Right now I’m in Maryland, and to be honest, I’d rather not be. But I need foot surgery — nothing as big as the one I had in 2017, which involved two incisions, four cuts through the bone, four titanium screws, and a bunch of toe ligaments cut and then sewn back together — but still significant enough that I’ll need to stay in a normal house, not a van, for a few weeks. (I was trying to make this surgery happen in Colorado: I talked to a couple of surgeons there, who gave me two different surgical plans and I felt uncomfortable with both. But the surgeon here in Maryland who did my other foot five years ago came up with a plan I feel pretty good about.)

I’m not excited about having foot surgery. I’m not excited about going for the whole summer without hiking or stand-up paddleboarding, and I’m not excited about being unable to do normal life things, like lugging a forty-pound jug of water from the spigot to the van or even taking a shower, without caution and deliberate thought. I’m not excited about all the rehab I’ll have to do on my foot, because that involves a lot of stretching and stretching is boring and I hate it. I’m not excited about being unable to exercise like I’m used to and losing whatever fitness I’ve gained in the last year. But all of this had to happen sometime, and now’s the time.

So I’m looking for the silver linings. For one, I’m grateful that I have option of being able to stay in my parents’ nice guest room while I recuperate, with my mom to make sure I take the appropriate dose of painkillers and bring me food and water. For another, I’ve been able to see some friends and family members in person for the first time since before the pandemic. And though this part of Maryland lacks mountains, it makes up for it with water, and I’ve been able to paddle and swim. I’ve spotted horseshoe crabs from my parents’ pier, a deer eating the old lettuce my mom threw out, a bluebird feeding its baby with a seed from the bird feeder. So right now I miss being in the wilderness — but I have wildness.

44 Wildernesses

I’m a sucker for maps.

Maps are mystery. Maps are potential.

Looking at a map, planning where I might go, what areas I think might be beautiful or interesting or might simply fill in the blank spots in my own mental map, is weirdly satisfying to me. I find looking at maps of places I might go hiking almost as good as actually being out there — or even better than being out there, if it’s chilly outside and I’m wrapped in blankets, daydreaming.

So check out this one.

This is a map of all the wilderness areas in Colorado, shown in darkest green.

There are a lot of them. Forty-four, to be exact. And last summer, when I was making loops all over the state, hyped up on the novelty of being able to go wherever I wanted, I decided: I’m going to hike in all of them.

It doesn’t have to be anything crazy, like an overnight backpacking trip or even an all-day thing. Just a mile or so past the wilderness boundary, enough to give me a taste of the place, will do.

Not only would this be fun, I figured, but it could be a helpful organizing principle. Sometimes having an enormous amount of options makes it paradoxically harder to make decisions. And trying to set foot in each of the wildernesses could get me thinking outside the scope of what I already know. So I figure that if I ever want to go someplace in Colorado that’s new to me but am not quite sure how to narrow it down, I can take a look at the list of wildernesses and go where I haven’t been yet.

So, you may wonder, since I spent like five whole months in Colorado last summer, and there are 44 wildernesses, and I just wrote in my last blog post about how I’ve been doing too much driving, I must have been to what, half of them by now? A third?

Nope! I’ve been to seven. (So that’s a tiny 6.29%!)

I’m not in a big hurry on this. I want to try to avoid the urge to rush from one place to another, and I want to drive less, like I mentioned. Also, I want to make sure that I don’t, just to give a totally hypothetical example that absolutely isn’t taken from my actual life at all, nope no sir not me, procrastinate from difficult good things like writing fiction by focusing on easier good things like hiking.

So here’s my list as it stands:

WILDERNESSES HIKED IN

Sangre de Cristo

- Venable Trail

Lizard Head

- Navajo Lake

- probably Lizard Head Trail crossed wilderness boundary

Holy Cross

- Timberline Lake

- St. Kevin Lake

Mt. Massive

- Windsor Lake

Flat Tops

- Chinese Wall

- Devils Causeway

Raggeds

- Raspberry Creek

Hermosa Creek

- Ryman Trail to Highline/CO Trail

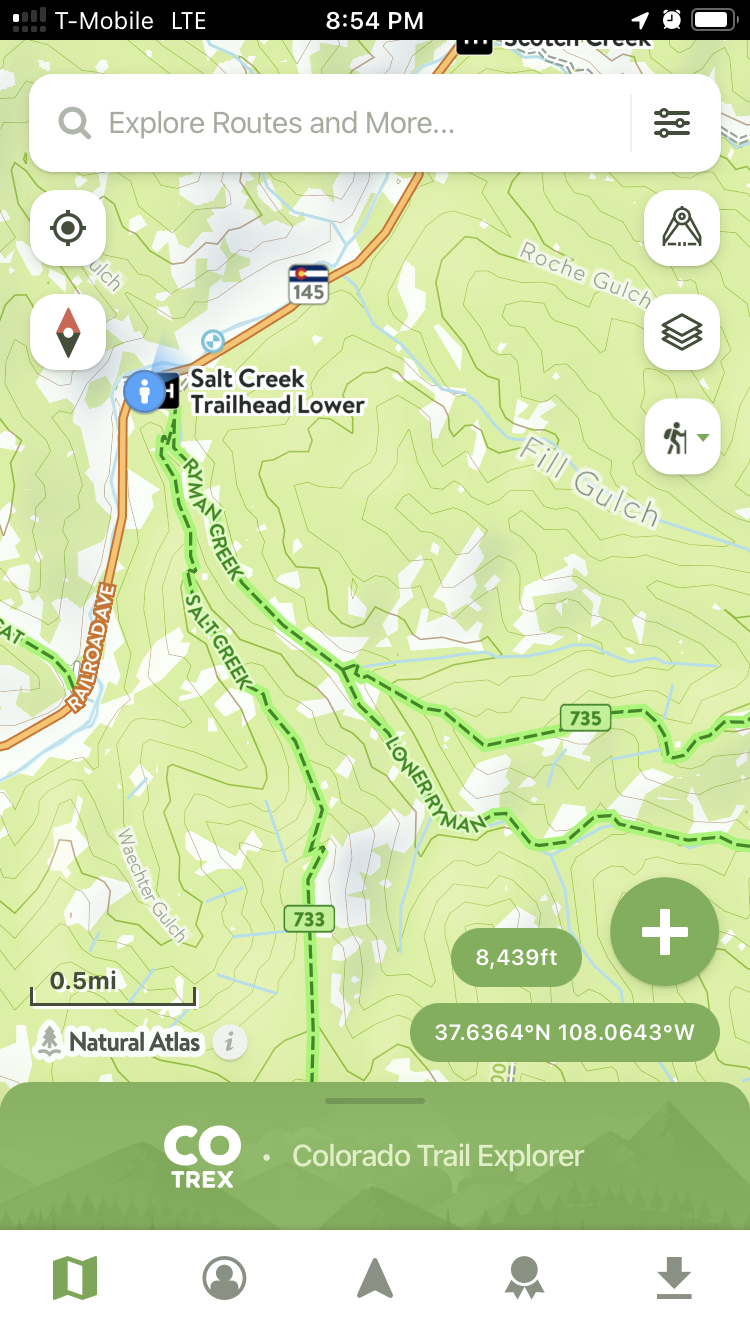

Let me tell you about the one I added to my list yesterday, Hermosa Creek.

This wilderness is in one of my favorite areas of the state: the San Juan range in southwestern Colorado. I’ve written before, I think, about the San Juans. They get a bit more summer moisture than some other ranges, so by Colorado standards, they’re very green, and the rocks and soil can be very red. They used to be volcanoes, and there’s something about the mud that is extra silty and sticky, so each of your boots end up weighing like five pounds. The western region of the San Juans, which is where I’ve spent the most time, also has some really sudden transitions from farmland to mountains or mountains to desert, and I am all about that drama.

I spent the first couple weeks of May in the national forest north of Mancos, so I wasn’t too far from the Hermosa Creek Wilderness, which is one I was very curious about. But it’s not easy to access. There are no roads close by on the east or north, and while there’s a road going towards it from the south, I went a little bit up that road last fall, and I suspect that the last few miles of it wouldn’t be navigable with my van. So I’d be walking a few miles along a 4wd road, possibly eating the dust of passing ATVs, which does not seem fun.

I opted instead to hike into the wilderness from Route 145 just south of Rico, one of my favorite mountain towns. (And where I’m parked now as I’m writing this blog.)

I’d take the Ryman Creek trail. As I headed east, I’d stay left at the fork to go on Upper Ryman, then turn right/south for just a teeny tiny bit until I got to the wilderness boundary. (Which is the line made up of a bunch of green dots in the lower-right corner of the second photo.)

This plan was a little tentative. There’s still some snow in patches high up, and I’d tried hiking Lower Ryman last fall and it was pretty overgrown. Also, a couple people on the Alltrails app mentioned that Upper Ryman was “steep” (which really could mean anything, from “a sphere placed on this surface would roll downhill” to “you will need to use your hands to climb up it”). I figured that if things got too tricky before I got to the wilderness boundary, I’d just turn around and at least I’d have a nice hike anyway.

I started out at the ass-crack of dawn, around 6 a.m., because even though I’m a natural sunrise-waker-upper and it takes some effort for me to get up before sunrise, once I’m out there and it’s still so early that the light is gray, I adore it. About a mile or so up, I came to my first obstacle.

Uh oh! It’s a spiky log!

The water in the creek was pretty high due to the snowmelt higher up. Last fall, I think I just stepped across the creek where it went between the two evergreens (upper left of photo) on some raised logs or sticks or hummocks of grass. But this time, it was either spiky log or get my feet wet. I opted for spiky log, and I did it!

Soon afterwards, I passed this sign.

I never did see any trail construction, but I did periodically wonder what the sign meant by “and even worse.” Did they mean that those who failed to obey the sign would be punished by a fate worse than death? Or just that a person could cause a rockslide and kill someone else, which might be worse for the rockslide-causer than if they themselves died? Or did whoever wrote this sign just want to keep us on our toes?

Then the steep part started. And it was steep. I didn’t have to use my hands, but I was hauling myself up using my hiking poles. And I did think, “this particular angle is the limit at which a human foot can maintain traction on this particular surface.” The trail surface was just dirt, which was sometimes loose and slidey. I would’ve had a much better grip if it was solid rock, or it would’ve been an easier climb if there were rock steps or switchbacks. But the trail went up a relatively narrow ridge, so in many spots there wasn’t even room for switchbacks. So the trail just went straight up the spine.

I didn’t take many photos because I was busy cursing and being out of breath and trying not to slip. It was really beautiful, though.

Once the steep section was done, I found myself in a magical aspen grove.

I took a break here to drink a bunch of tea and eat a snack. The birds had woken up in earnest when the sunlight hit the ridge, so I was using this new app that I am obsessed with that identifies birds by sound. There were some sweet little warblers, a northern flicker, and a flock of at least half a dozen violet-green swallows. These swallows were wonderful to watch, darting and banking and diving and soaring out over the creek valley. I don’t think they were catching bugs, not as early and chilly as it was. I’m sure that a bird behaviorist could explain why they were doing that and that it must have a survival function—reinforcing group roles and hierarchy, or competing for mates, something like that—but it looked like exuberance, like play.

Definitely not my photo, but just so you can see how gorgeous these birds are:

The top of the ridge was mostly aspen (with a few stands of evergreens) for miles. It was just beautiful up there, and I had some interesting wildlife moments. Tons more birds, for starters. Then I heard a snap or crash and in the distance between the trees saw something large and brown running down the hill. It was either a deer, elk, or bear—all of which had left tracks on the trail at some point—but it was clearly aware of me long before I was aware of it. Later on, a hummingbird came out of nowhere and arrowed towards me. I thought it was going to pass over my head but it stopped, going sixty to zero, about two feet in front of my face, and stared at me, flaring its tail. Then it zipped away. For the Aztecs, hummingbirds and warriors were connected, and this makes total sense.

The aspen trees were heavily marked, and most of those markings were so old they were no longer legible. I get the sense that decades ago, this trail saw heavier use than it did today. I’m not keen on people carving their names into trees, but it is pretty impressive how old some of these trees are!

I kept going gradually up, passing the turnoff for the Lower Ryman trail, and then there was another, shorter section of steep climbing. More of the surrounding ridges and mountains came into view—off to the south, I could even see Dibe’Nitsaa (aka Mt. Hesperus), which is a few miles away from my last campsite north of Mancos.

Then I came to the next obstacle:

There was snow covering the trail. I thought, if it’s like this the whole way, I won’t be able to slog through it all. I might have to turn back. Fortunately, the snow was just a few patches, 10-20-30 feet long, and it was still frozen solid enough at that point that I mostly just walked over it.

Then it all happened very quickly: I got to the forest service road that led to the Highline Trail/Colorado Trail. Then I was at the Hermosa Creek Wilderness boundary!

I know I said that I liked to walk about a mile past the boundary. But the trail here never actually crosses it, and it was a fairly long hike to even reach the boundary. So in this case I was content with just walking around the sign.

But the big thing happening here was the views.

Enhance!

I mean, why? Why is it like this??

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

[inward shouting of incomprehension and delight]

But because language gives us a tool to make sense of things, I can say that part of what boggles me about a mountain range like this one is that there’s both incredible scope and incredible intricacy. Like nature should be exhausted after making *one* mountain that complex and that huge, but there’s another and another and another and…

And there’s also the time scale: the knowledge that in the deep past, if you could sit where I was sitting and watch that specific sector of the horizon for ten years, twenty, a whole lifetime, probably nothing visibly dramatic would happen. And yet, the drama! It looks like they just popped out of the ground last week, all crowding together in their eagerness to start being mountains and do an EMPHATICALLY good job of it.

And because one way we engage with mystery is to make maps, and measure things, and give the mountains names, even when there are so many and they are so big, I can tell you that the mountain range in the distance was about 20 miles from where I was sitting, that on the map it’s called the Needles range, and that these are some big honking mountains.

Even though I could’ve stayed there for hours, after about 45 minutes of sitting and looking and eating a couple of tortillas with peanut butter, I had to start back. I picked up a couple pieces of litter (yes, even all the way up there), tried talking to a raven, and it was literally all downhill from there.

Also literally, it was a very enjoyable walk downhill. I did encounter a few obstacles:

The snow had softened, so it didn’t hold my weight so well and I postholed through it thigh-deep a few times. Totally worth it.

I slipped crossing a tiny stream and landed on my ass in the San Juan mud. Also totally worth it.

Going down the steep sections of the trail was trickier and more dangerous than going up, and my feet went out from under me once or twice. Fortunately I didn’t hurt myself, and still totally worth it.

I’m a slow hiker, I stop often to stare at things, and I take long breaks, so about 12 hours after I left the van, I came back to it tired, hungry, muddy, exhilarated, and content.

So that’s how I hiked into my seventh Colorado wilderness. Here’s to 37 more.

By the Numbers: One-Year Retrospective

This past Sunday (May 8) was Mother’s Day this year, but it also happened to be my one year (v)anniversary of living full-time and continuously in van v2.0. Counting the time I lived in v1.0 (September–December 2020), it’s been 16 months. So it seems like a good time for a very math-y perspective on how it’s going so far.

I had to start by thinking about miles traveled. Since I bought the van with (I think) about 298,000 miles on the odometer, I’ve put about 31,000 miles on it, averaging 1,937.5 miles per month. Given that the average driver covers a little over 1,100 per month, that’s a lot.

It also means I’m generating about 2,700 lbs of CO2 emissions each month, which—well, I’d really rather not. (I’m paying a shockingly low amount ($23) per month to offset 5,000 lbs of CO2 through Terrapass, though I’m not sure how effective this carbon offset program or any other program is at compensating for the damage I’m doing.)

I tried to use Google Maps and then Mapquest to draw my approximate route since May 2021, but Google Maps wouldn’t let me add enough stops and Mapquest failed to compute the route past November 2021. So you’ll just have to imagine it:

I’ve been as far northwest as Seattle; as far southwest as Death Valley, CA; as far southeast as metro Tampa, FL; and as far northeast as South Jersey. Colorado would end up looking like a hub: and I’ve looped around the mountain ranges in the north and south of the state. I’ve also made sort of a Y-shape in New Mexico and visited Capitol Reef and Arches National Parks in Utah.

Am I Better Off?

When I decided to move into a van, I was hoping for a couple of things: a) that it would help me save money, or at least break even, and b) improve my quality of life.

So it’s time for some van-cost calculations that I’ve put off for a year, simply out of dread of what I’ll see when I look through my old credit card statements: the fast-food breakfasts; the four single-serve kombuchas in a two-week period when a large bottle would have been cheaper and buying none at all would have been more responsible; all the orders from mega-retailers that are destroying individual lives and the world in general and profiting space billionaires; and my general moral decline from my financially-disciplined, I-know-where-every-cent-is-going teens and twenties into my weak-willed, effete, flabby middle age.

But deep breath. Here goes.

Did I Save Money on Housing?

Base cost of van (purchase, registration, initial repairs): $2,801.17

Professional help with build (solar, removing rear AC/heat units): $1,898.72

Build supplies (including lumber, battery, fan, insulation, hardware, mattress, etc.): $6,764.54

Repairs, maintenance (not counting oil changes), upgrades (fancy tires): $3,685.39

TOTAL: $15,149.82

Honestly, despite my initial hope of keeping the whole van under $10k, $15k is about what I was suspecting. And I’m guessing it’s more than I’ve spent, total, on all the other cars I’ve ever owned in my life. (Which were all compact sedans or hatchbacks that I bought used and drove until the wheels fell off, metaphorically speaking.)

So to me, $15k sounds pretty cheap for a house… but a LOT for a car… but cheap for a house! I don’t know what to think!

But I still need to factor in travel costs. Some Googling and some very loose math tells me that the average cost of gas since September 2020 has been $3.50.

Doing another calculation I’ve been dreading, I find that the van gets an average of 13.24 miles per gallon, which is not as bad as I was afraid of, but not great.

31,000 miles @ 13.24 per gallon = 2,341 gallons x $3.50 = $8,193.50

So here’s the grand total cost of living in a van since September 2020:

Van total: $15,149.82

Driving all over the place: $8,193.50

Campgrounds (estimate): $520

—————————————————————

TOTAL: $23,863.32

Now let’s compare that to what it would’ve cost me if I stayed in my Denver condo. I’m assuming that I’m spending about the same on food, entertainment, healthcare, laundry, car insurance (the van is a little more than my old car, but not that much), etc.

Condo mortgage + HOA fees + average electric, September 2020-present: $715 x 16 = $11,440

OK, so that sucks. Living in a van has not saved me money on housing.

In fact, it’s cost me $12,423.32 more.

But the van had some big initial costs that I hopefully won’t encounter again, like the initial purchase price and all the stuff for the interior build. So is there ever a point where I’ll break even financially?

Yes, there is. But—assuming that I continue to drive an average of 1,937 miles/month, that the price of gas stays the same as it is right now ($4.10), and that my condo HOA fees would not have gone up—the break-even point won’t be until 2031.

:/

But what if I drove less? Say I could reduce driving by 1/3. That moves the break-even point to 2026. Which is better than 2031… but still not super.

Things become slightly better if I reduce driving by 1/2: I’d break even in early 2025. The same could happen if I reduce driving by 1/3 but gas goes down to $3.50/gallon.

So the news here is not great: If I ever want to break even, I need to start driving less.

Did My Quality of Life Improve?

So all my cost estimates assume that nothing major will go wrong with the van (knock on wood) and that nothing major would have gone wrong with my condo. It also assumes that if I’d stayed in the condo, I wouldn’t have traveled beyond some occasional day trips or camping trips into the Colorado mountains.

Which brings me to the next question: has living in a van been better, in other ways, than living in a condo?

I wish I could do math for this too. (And if you know of a more rigorous way to measure quality of life, message me!) But all I know to do is make an old-fashioned pros and cons list:

Living in Condo

Living in Van

It’s tough to make a meaningful comparison here without the ability to see into a parallel universe where I’d stayed in the condo. Maybe, in the last year-plus, I would’ve found some ways to alleviate the negatives of staying in the condo: maybe an amazing career opportunity would have opened up, quieter neighbors would have moved in, or something totally unexpected and great would happen.

Also, it wasn’t a binary choice between van and condo. I was considering some other options, like moving onto a boat in Baltimore or a small house somewhere in the desert or the rural midwest. Maybe those options would’ve been much better than the van… or much worse.

All I know is that even though I’m pretty disappointed that I’m not saving a ton of money over the condo, I feel like my quality of life is better than it would’ve been if I’d taken the other, obvious path of staying put. Even though the van has a ton of drawbacks, the positives have some heft to them. My stress level seems lower than it was when I lived in more “normal” places. I think I’ve gotten healthier and am in better shape. And I enjoy being “at home” more. (And if I decide that I need to make cutting costs more of a priority, I can quit at any time! Really! (Do I sound convincing? I’m not so sure that I do.))

I’ll end with a caveat, if anyone is reading this out of curiosity about what a nomadic life costs: this blog post uses a sample size of one to obtain its data. I imagine that some people spend much more every year; I know for a fact that many spend far less. The Homes on Wheels Alliance (HOWA) is a great resource for nomadic life on a budget. One of their videos features a guy whose total expenses (minus the initial cost of his RV) are under $4k/year, and other folks talk about how they live within their means on fixed incomes like social security. (The Glorious Life on Wheels channel also features folks on fixed incomes and talks about how that works.) So low-budget vanlife can be done… I’m just not doing it.

Big August

The US norm of only two weeks’ paid vacation — IF you’re lucky — is a scam and a scandal. It plays into the lie that there’s not nearly enough money to go around and only our nonstop toil can keep the feebly flickering economic flame from going out. There are plenty of other developed nations where regular people have access to functional and humane healthcare systems, paid family leave, and weeks or even a month of paid vacation, minimum, and those countries’ economies are doing fine. We’re the ones who have it backwards. We should take vacations. And as someone who is self-employed and works remotely, I have some flexibility to live according to how I think things should be, to normalize long vacations by taking one of my own. But it still felt very weird when I emailed my regular clients earlier this summer and told them I’d be unavailable most of August.

This plan started in the spring when my friend Melissa planned a big family trip to Glacier National Park in Montana — her husband and kids, parents on both sides, some in-laws and cousins, and me. When that big vacation was established, two smaller ones clicked into place on either side, like a set of magnets. Seattle was only a day or so out of the way — I could visit my friend Julie for a long weekend and do some paddleboarding. And then the Santa Fe opera season’s last week was the week after the Glacier trip, and my friend Ron had always wanted to see Eugene Onegin.

So I was planning to make a big loop around the west: Colorado to Seattle to Glacier to Santa Fe. The vaccines were out and available to everyone, covid rates were dropping, and it seemed like this trip would be a tripartite celebration with three groups of friends: a victory romp, a big shout of joy, now that we were finally on our way to beating the pandemic.

We could’ve beat the pandemic this year. But of course we know how that went. My friends and I kept our vacation plans, though with precautions, like N95s on planes and carryout in lieu of actually going out. But it was still a great trip(s), fully worthwhile and lovely.

If you (like many people, sometimes including me) get bored listening to people exhaustively describe their vacations, please feel free to skip this post. I’m planning to write about some more topical stuff this fall, like whether living in a van is actually cheaper than living in a regular house, whether it’s more sustainable, and which of my van design choices have worked out well and which are flopping. But if you want the vacation narration and/or photos, read on!

PART I: SEATTLE

Starting in southwestern Colorado, I drove through Boise and parked the van by some lava rocks near the highway. There were fires all over the west, so I kept checking fire and smoke maps on my phone, trying to figure out where I could stop to avoid the worst of it. The drive was hazy basically all the way to Washington, and the sunsets and sunrises were all pink and orange.

On my second day of driving, I made it all the way to western Washington. I’d given myself three days to get there and it was only Wednesday, so I was basically early for my weekend plans with Julie. I had work to finish up anyway, so I plopped myself down among some big, gorgeous trees in the Cascades west of Yakima and figured I’d stay there until Friday or Saturday.

The next morning I was working away in the van and realized the light was weird. It was very orangey, and something about it was just slightly off. Also, my eyes itched and my head hurt a little.

I checked the fire maps, and sure enough, at about the time I arrived the day before, a new fire had started directly north of me. The smoke was billowing overhead just to the east. On my phone screen, it was a plume of bright red pixels, expanding and darkening to purple as the 24-hour forecast map ticked into the future.

I really liked this campsite, so I tried to stick it out for a while, but I finally drove off to the west, where the smoke wouldn’t be as thick.

I ended up driving quite a distance. The smoke cleared. At one point, I rounded a bend and wondered, “Why do the clouds up ahead look weird?”

Then I realized that what I was looking not at clouds but at the side of a mountain with patches of snow, a mountain so big that at first I did not notice that it was a mountain.